Our first full day in the United Kingdom was a Tuesday, the starting day of Liz's work conference. We woke up and had breakfast together in our hotel, then I drove Liz over to Ashton Gate Stadium where she would be spending most of the day at her event. This left me free to be a deadbeat husband and spend the next few hours off sightseeing before returning to get dinner together in the evening. I had researched different attractions to visit in the vicinity of Bristol and decided that I would focus on two famous cathedral towns nearby: Salisbury and Winchester. Neither of these locations are particularly famous today, however these were powerful and important religious centers during the medieval period. Going back even further than that, I planned to stop on the way to Salisbury at the tiny village of Avebury which hosts a prehistoric stone circle even larger than Stonehenge. This was a bit of an oddball day of tourist attractions linked together by this common theme of visiting places with a strong spiritual connection.

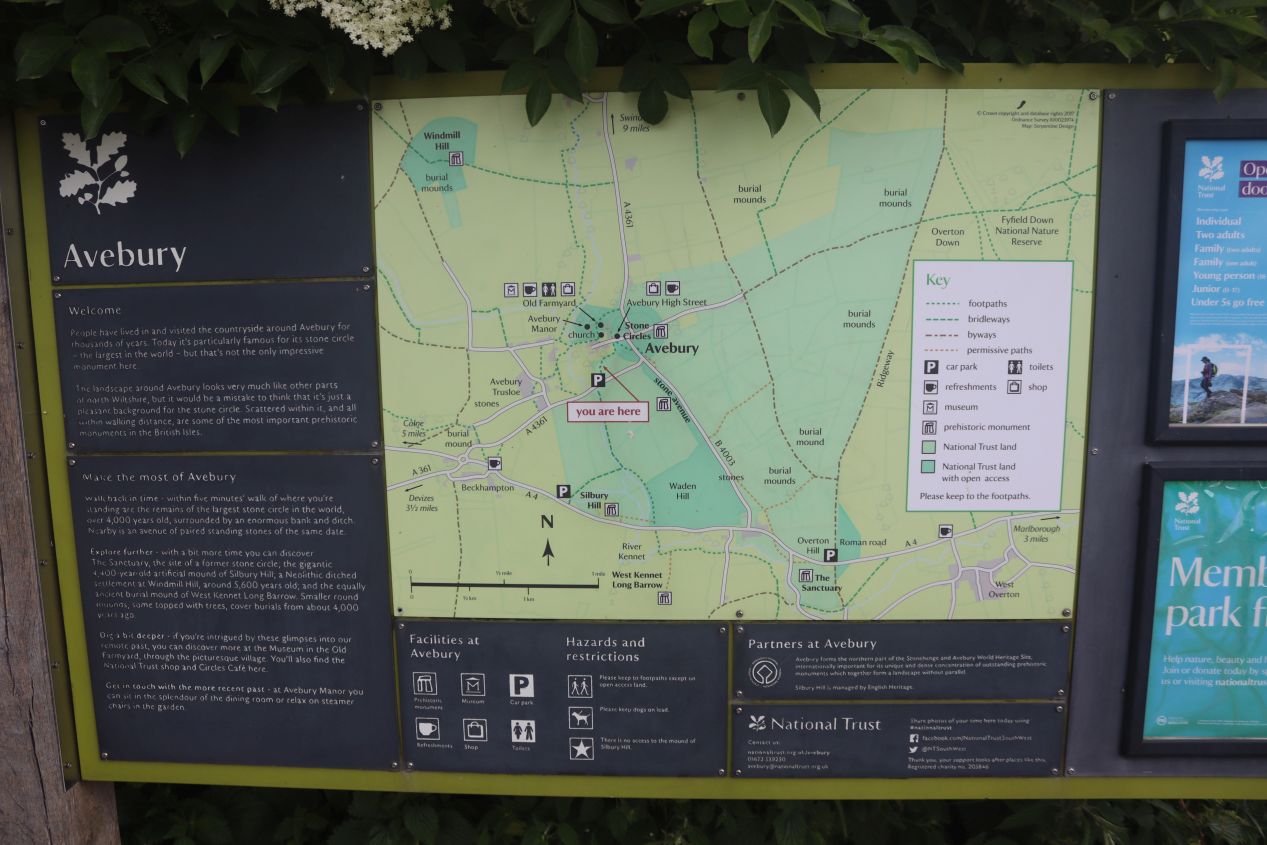

It took about an hour's worth of driving to travel from Bristol eastwards to Avebury, which was basically located in the middle of nowhere surrounded by various farms. I'd been able to take the M4 for a while out of Bristol before eventually having to turn onto another one of those narrow local roads barely wide enough for two cars which took me the rest of the way to Avebury. The little village was so small that it only had a couple of roads and lacked even a single traffic light; I drove through the whole thing in less than a minute before turning into the parking lot for the stone circles. From there it was a short walk to this visitor reception center which was located in a huge barn. Here I was able to get some more information about the area and see the walking path that led to the main attraction, the prehistoric stone circles themselves:

I mentioned how the stone circles at Avebury are considerably larger than Stonehenge, if nowhere near as well preserved or as famous. In fact, the ancient stone monuments are so large that the village of Avebury was literally built INSIDE the circle itself. This is best seen when looking at aerial photographs of Avebury so I'll grab one off the Internet and include it above (I did not have access to a plane, helicopter, or drone for this trip). As seen from above, there was a gigantic earth mound built in a wide ring with stones running around it, then later the medieval town of Avebury grew up inside the circle, followed by much later by the addition of a modern road that cut through near its center. The whole thing was wild to see and it's a bit surprising to me that Avebury isn't better known as a tourist attraction.

My pictures were all taken from ground level where visitors could walk right up to the ancient stones and reach out to touch them. As at Stonehenge, researchers believe that the Avebury stones circles were constructed in different stages over a long period of time spanning roughly 3000-2500 BC. The henge at Avebury is not perfectly circular (unsurprising given its extreme age) and stretches some 350 meters / 1150 feet in diameter from one end to the other. It's unclear exactly why Avebury's stone circles were built but they likely had some kind of religious or astronomical significance. For a modern visitor, it was quite relaxing to stroll between the big stones and think about just how ancient their construction had been. (To be fair, most of the stones were previously knocked over, either accidentally by the passage of time or deliberately by superstitious townspeople, before being raised again in recent decades.) There certainly was hardly anyone else here in contrast to the big crowds that we had seen at Stonehenge the day before.

The gentle walking path at Avebury followed the course of the stone circles in a big arc, running past a series of fences and eventually through the little town square. There were lots of sheep here in this farming community, apparently being kept in pasture right next to the ancient stones. Don't mind those 4500 year old monuments right next to where the sheep were grazing, heh. This is a little bit like someone herding cattle right next to the Great Pyramids at Giza. In the center of town was the only restaurant that I could find, a pub known as the Red Lion which looked like a lovely place to get a meal. I would have happily eaten here if Liz had been with me but it wasn't somewhere I wanted to stop as a solo traveler. Then there was also a small chapel nearby which dated back to 1707 and which I tried to enter only to find that it was locked. Again, all of these buildings were situated inside the stone circle which was easy to forget due to its immense size.

These were a few more pictures of the standing stones as I finished up tracing the big loop around the circle. The Avebury location has quite a history as this spot was clearly very important in the prehistoric period, only to be abandoned sometime around the start of the first milennium BC. (People often associate these stone circles with the Celts or their druids but that's a mistake; they were built by even earlier inhabitants of the British Isles. The Celts wouldn't have had any idea what these stone monuments were.) Avebury was then resettled at some point in the early Anglo-Saxon period as there are records indicating that a handful of people were living here by the 9th century. The stone monuments were seen as being associated with the Devil since they were clearly non-Christian in nature but the local villagers didn't have the resources to do much about them. There was an attempt to tear down the stones around 1320 but apparently someone was crushed underneath one of the stones in the process, which scared off further attempts for several centuries (and also led to more certainty that these were the work of Satan). Then many of the stones were torn down in the early modern period, with its obsessive focus on witchcraft, but fortunately enough have survived to be restored in the current period. It's quite a long history for such a little farming town.

I walked through the remainder of the town of Avebury before heading back to the parking lot with my rental car, finding a few more locations of interest along the way. One of these was Avebury Manor, a 16th century manor house which has been refurbished in a number of different styles over the centuries. Avebury Manor is usually the other main tourist attraction to be found here, however it was hit with serious flooding early in 2024 and remained closed for repairs at the time of my visit. I could see the building through a fence but that was it. I also came across the parish church, St. James, which had a great feel of age to its stone construction. The doors to St. James were somewhat surprisingly open and I found myself able to go inside and snap some pictures with no one else present. There are parts of this building that date back to the 10th century and much of what still remains is from the medieval period. I found the small size to be charming and it was clear that this place was still very much in use by the local community; this hand-knitted banner was a sign that someone really loved the parish church. I always enjoy getting to travel and see these small snippets of how people live in different parts of the world.

That was everything to see in Avebury which again was so miniscule that I could walk across the whole village in one or two minutes. Salisbury was only about 30 miles / 45 kilometers away directly to the south but it took nearly an hour to get there because I was driving the whole way on country backroads. They were quite pretty to experience, lots of rolling hills dotted with crops or grazing livestock, but my goodness were the roads ever narrow! They were barely wide enough for two cars to pass one another and every turn around a blind corner felt like a potential car crash waiting to happen. I made it to Salisbury in one piece but this was absolutely not an easy or fun drive to experience.

Once I reached Salisbury, I drove to the historic center of the city where its cathedral awaited. Salisbury Cathedral was visible off in the distance long before I arrived thanks to its central spire which at 404 feet / 123 meters is the tallest church spire in England. The cathedral was situated in an open grassy area known as the cathedral close, also the largest to be found in England, which looks much the same today as it did in landscape paintings from centuries earlier. Salisbury Cathedral is unusual for having been constructed over a short period (by medieval standards anyway), with most of the structure built in only 38 years between 1220 and 1258. This gives the cathedral a unified design as opposed to many of the other cathedrals which took centuries to build and wound up with various mismatched features. Salisbury Cathedral is therefore considered to be the ideal example of Early English Gothic design, often imitated elsewhere without being duplicated.

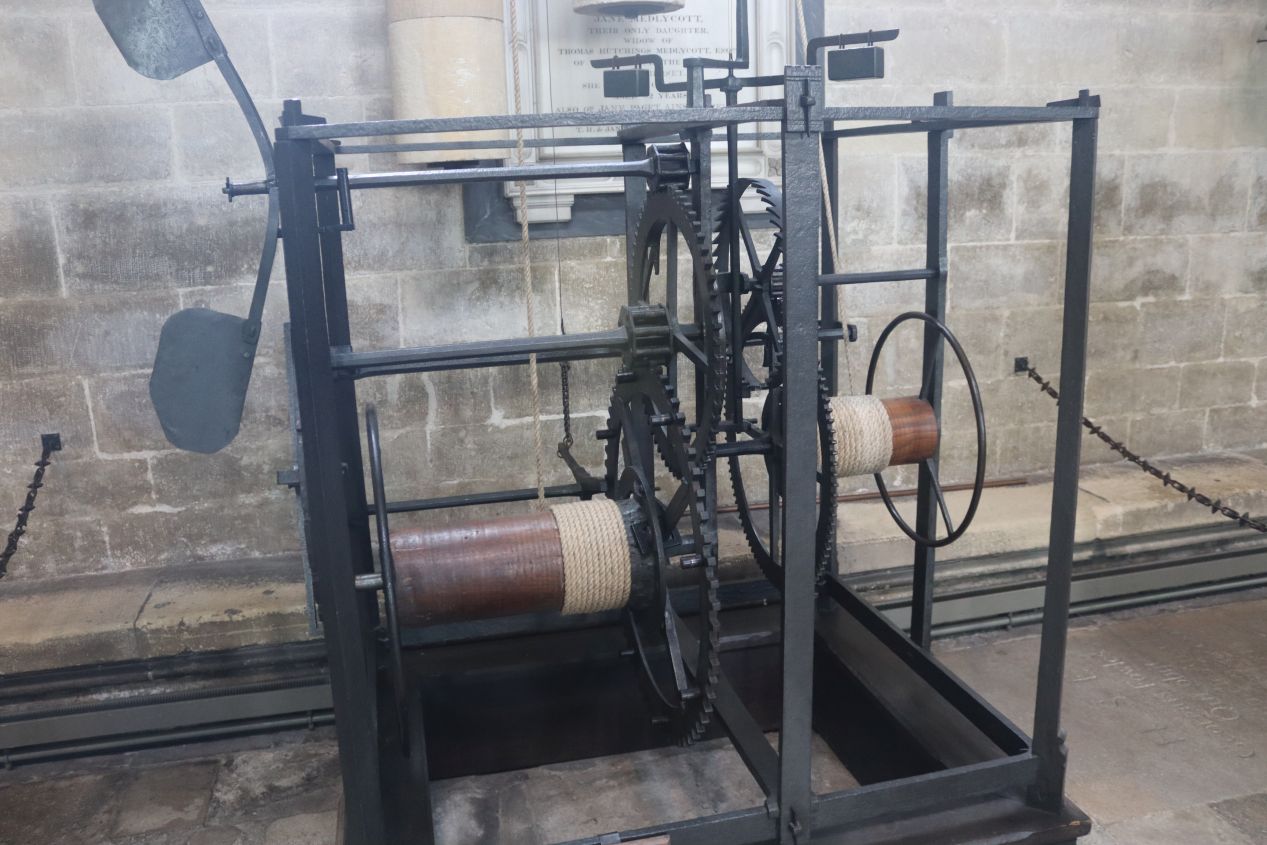

The cathedral wasn't too crowded on this beautiful weekday in early June, with only a modest flow of tourists like myself and some school groups waiting outside, which allowed me to purchase an entry ticket without needing to wait in line. The interior of the cathedral had the standard Gothic design with two rows of stone pillars on either side holding up the weight of the building, with very tall vaulted ceilings in the center and stained glass windows on either side to let in light. Since this was one of the famous cathedrals that helped set the standard elsewhere, it made sense that Salisbury followed the general pattern for cathedral design. Near the western entrance and off to the side were two minor items of interest. One was a little diorama showing what the cathedral would have looked like when it was under construction in the 13th century, with great attention to detail on the little workers hammering the beams into place. The other attraction was something advertised as the world's oldest working mechanical clock. Dating from about 1386, the clock had no dials or hands and told time simply by striking a bell every hour. It was an impressive sign of medieval ingenuity that heradled the onset of the Renaissance just beginning to appear in Italy.

As usual when visiting a cathedral, I walked towards the central altar by heading down the left side of the building. This brought me to the main transept, the side "arms" of the cross in a standard cruiform Gothic cathedral design. Salisbury Cathedral actually has a double transept with a second set of side corridors a little further up from the main nave. There was a huge amount of open space here beneath the tall ceilings, with several side chapels and of course more stained glass windows that ran up the sides of the walls. The center of the nave held a modern font which was only installed in 2008 for the cathedral's 750th anniversary. This is the largest working font in any English cathedral and stretches some 10 feet across with continuous flowing water running to the floor below. Even though this was a modern addition to the cathedral, it did not look out of place in these surroundings.

The central part of the cathedral right where the transepts joined the main nave held my favorite part of the design: the choir. There was a beautiful modern octogonal altar situated here and then the wooden rows where the choir would sit were located immediately behind it. High above overhead, the ceiling in this part of the cathedral was richly painted with colorful depictions of what I imagine were the saints or apostles. This is one time where it was worthwhile to break out the telephoto lens from the camera bag that I was lugging around so that I could zoom in on the details of those paintings. Modern cell phones do a great job with taking pictures but there are a couple situations like this where a traditional camera still works better.

More details showing the choir portion of the cathedral which seemed to be the central design motif of the whole building. The wooden rows of the choir looked like something out of the Harry Potter movies... which of course they should since that book series was based on traditional English boarding schools which themselves imitated the religious architecture of places like Salisbury Cathedral. The attention to detail continued to be impressive with family coats of arms decorating the backs of the wooden rows and carvings of angels adorning the posts. Back behind the choir was another altar made from stone with dark blue and purple stained glass framing it from the exterior wall beyond. This stained glass looked different from the glass used everywhere else in the cathedral and I suspect it was added sometime in the modern period.

Like most other big Gothic cathedrals, there were a series of smaller side chapels here at Salisbury which I captured in a few of these pictures. I remember visiting Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome where there were a dozen masses being said continuously in all of the various chapels to cater to the pilgrims arriving from around the world. None of these chapels were in use at Salisbury at the time of my visit but I could see how they would be useful for smaller private services which didn't require the massive full cathedral. The last chapel was even dedicated to my namesake, Saint Michael the Archangel, and used as a place for prayer to all those caught up in warfare.

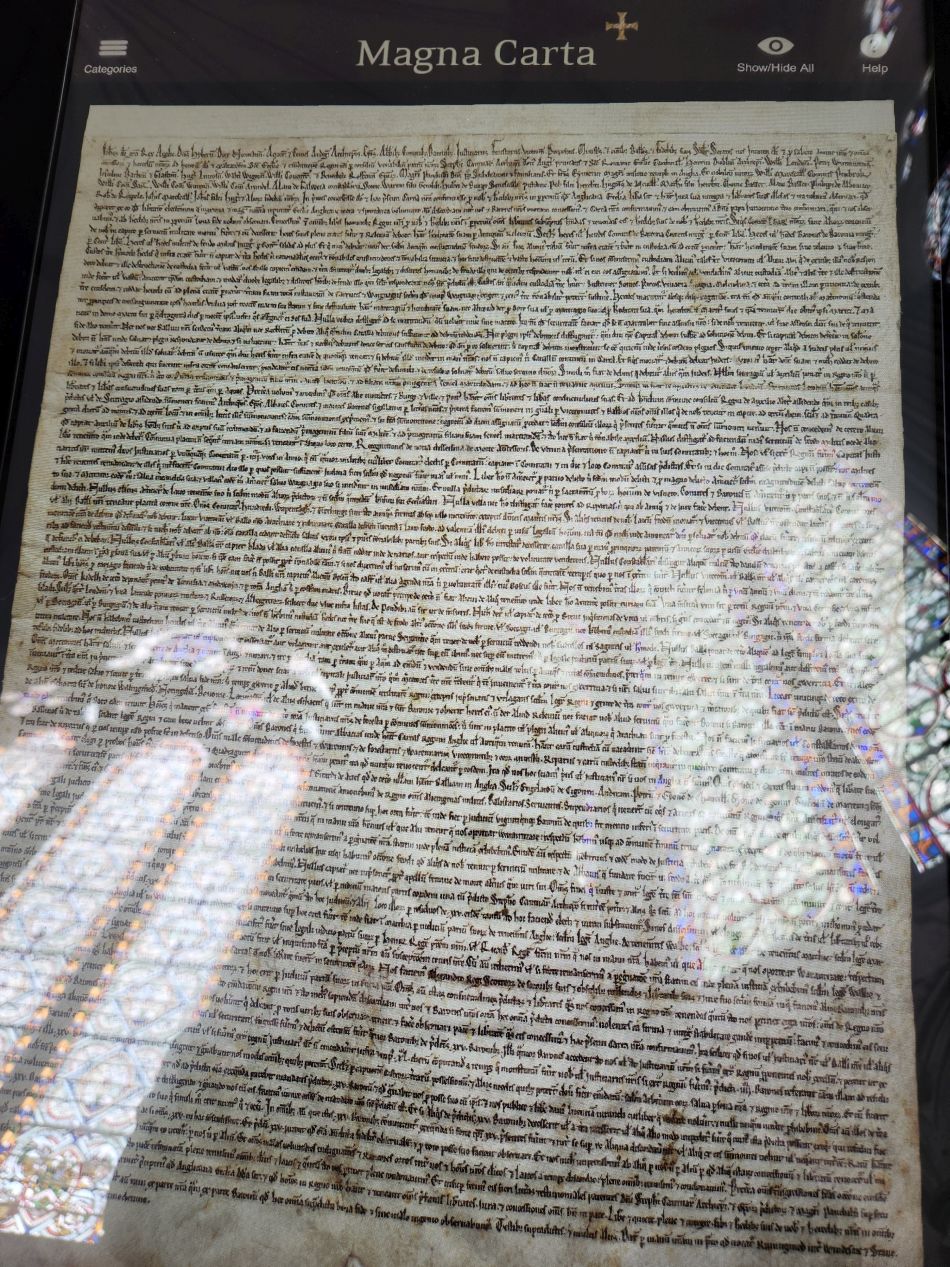

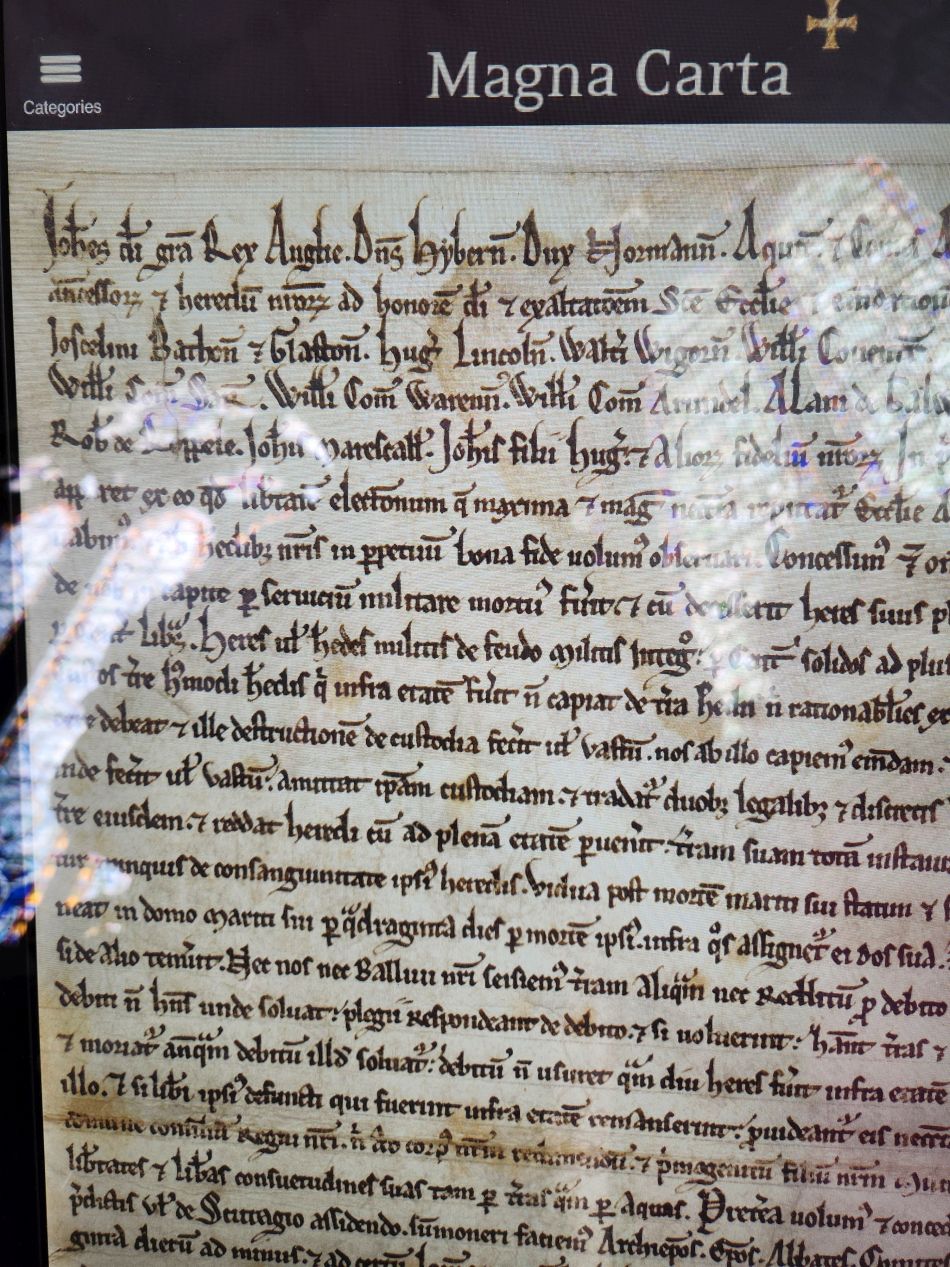

That was the extent of the main cathedral but there was another item of great interest to be found in one of the side cloisters. After passing along the enclosed green space, I was able to enter the cathedral's chapter house which holds one of the four remaining original copies of the Magna Carta. This is the famous Great Charter that King John was forced to sign by his rebelling barons in 1215 (and which he immediately tried to weasel out of afterwards), widely seen as one of the founding documents of constitutional governance in the English tradition. The chapter house itself was a beautiful small chamber with delicate stained glass comprising most of the walls, a design that reminded me of Sainte Chapelle in Paris. The room was completely given over to an exhibit on the Magna Carta, explaining what the document was and how it was made using parchment.

The original copy of the Magna Carta is stored in its own special little booth to protect it from sunlight, and of course photography of the document is not permitted to help keep it safe for future generations. Fortunately there's no need to photograph the ancient document because the chapter house also contained several digital copies that look completely identical and which allow visits to zoom in on the text, click on words for additional details, and so on. That's where these pictures were taken and I enjoyed getting a chance to look at the fine details of the document. The Magna Carta was written in Latin and uses a medieval script that's difficult for modern readers to understand; fortunately there's an English translation posted right next to the screen to make it easy to follow along. Most of the document is taken up with period-specific details about early 13th century English politics that don't have much interest to current readers, but the priciples at stake (that the king had to rule through consent of the governed) was what make Magna Carta an important document. This was the second copy of Magna Carta that I had seen, as there are two other original copies in the holdings of the British Library where I had spent a great deal of time (and then the fourth and final one is in Lincoln Castle which I definitely hadn't visited).

These were a few pictures that I took while walking around the historic part of Salisbury near the cathedral close. Salisbury is a small city with a population of about 40,000 at the time of writing and it has always been dominated by its cathedral since its founding in the 13th century. This city has a bizarre history as it was originally known as Sarum and located on top of a hill a few miles to the north. Due to feuding between the bishops of Sarum and local lords, the entire town was moved down into a nearby river valley where the current cathedral was built and the city of New Sarum (later Salisbury) grew up around it. In the modern period, Salisbury was known for its cutlery industry although today it has shifted over to a largely service economy. I took these pictures on High Street leading north out of the cathedral close as it passed through the High Street Gate, with the heart of the city's shopping area located on the other side. There were a series of museums just off the cathedral close nearby, one of them dedicated to the Berkshire and Wiltshire rifles and another one comprising a 13th century medieval hall which could be rented out as an event space (and which wasn't open to the public on this day). I didn't have a lot of time on hand but I did stop at another museum:

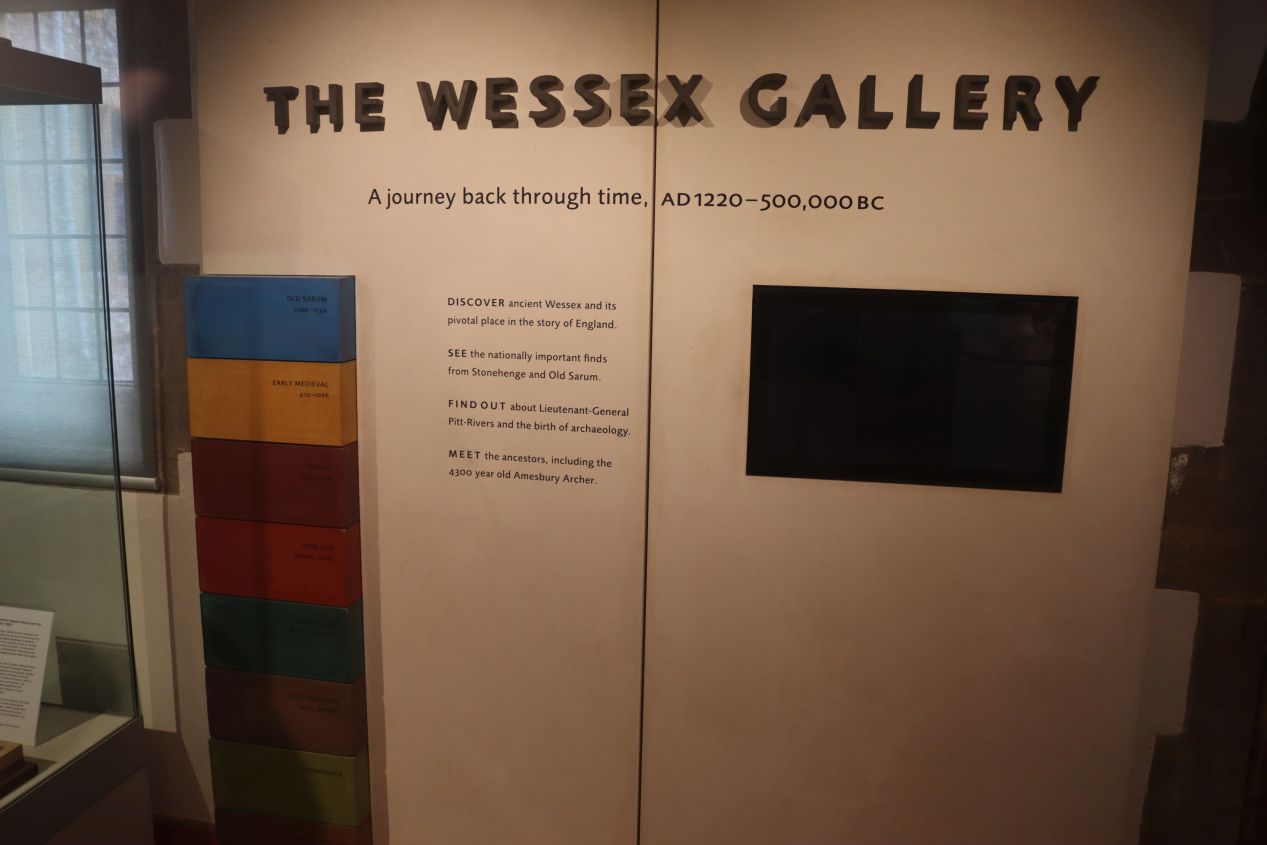

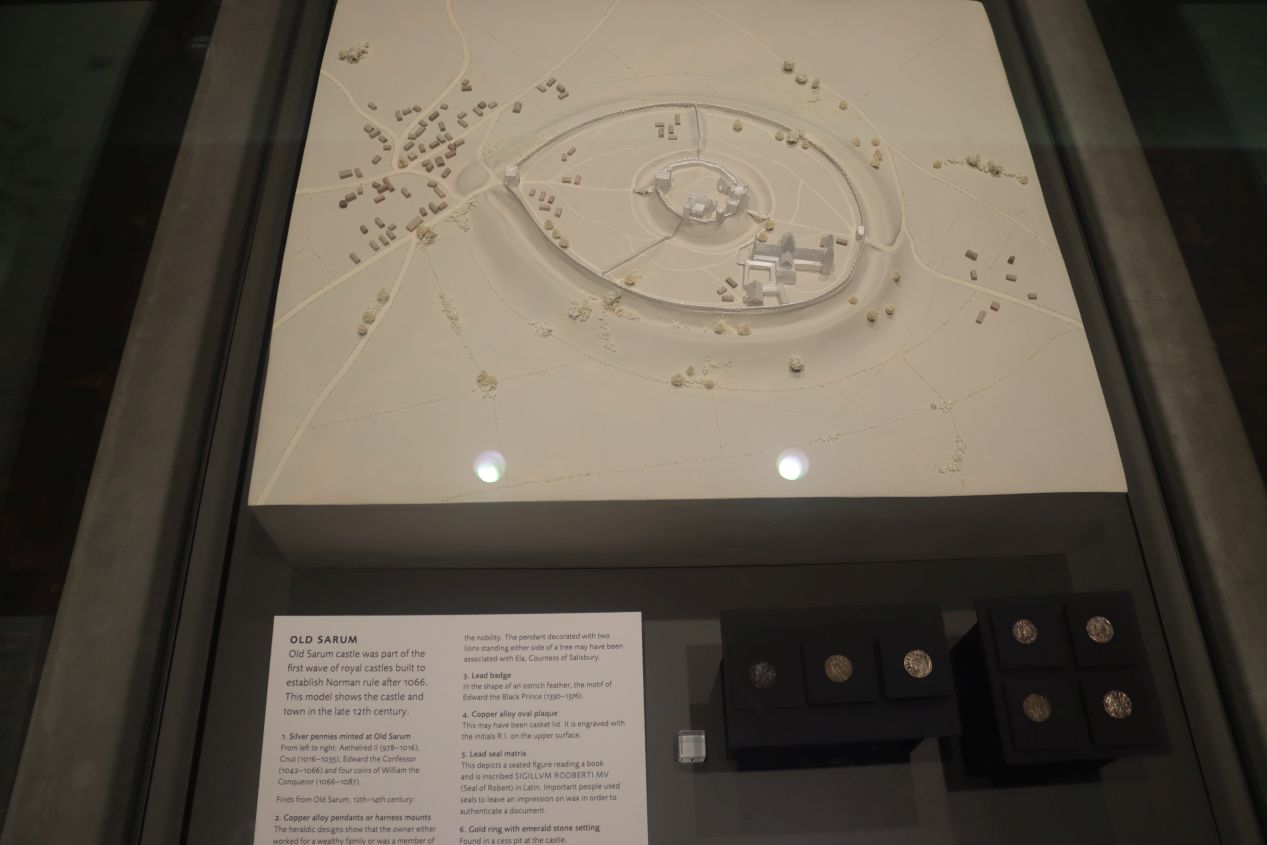

This was the Salisbury Museum, a local enterprise dedicated to showcasing the archaeological history of the surrounding region. There was a temporary exhibit here showcasing a 20th century artist called Rex Whistler, however I didn't really care about that portion of the museum and the exhibit has already ended by the time that I'm writing this report anyway. I was much more interested in the permanent exhibit here called the Wessex Gallery, which amusingly was divided into eight sections with the two "youngest" periods being Old Sarum (1066-1220) and Early Medieval (410-1066). This was a sign that the museum was mostly based on archaeological finds from the Neolithic period of Britain, and it turns out that the Wiltshire area has been a rich place for those finds. Salisbury is only a short distance away from Stonehenge and there have been dozens of burial mounds and various henges discovered in this region. Lots of those findings were on display here and I wish that Liz could have been present with me since she spent a lot of time studying archaeology in college.

The Salisbury Museum was laid out in chronological order starting with the earliest settlement of southern Britain and then concluding with artifacts from Old Sarum from before the town moved to its present site. There was the usual pottery on display (first rule of archaeology: it's always about the pottery) along with an unusually large number of human skeletons. These were the rather morbid results from a series of excavated burial mounds, and the museum had about half a dozen skeletons exhibited along with the various objects that had been buried along with the deceased. These ranged from early hunter-gatherers to an early medieval warrior from the 7th century. There were also a number of finds from the Roman period of British history, including this elaborate mosaic from the 4th century. Finally, I was intrigued by the coins, pottery, and statues salvaged from the Old Sarum location and put on display here. It still seems completely insane to me that the whole town moved to its current location in the 13th century and the ruins of Old Sarum can still be visited nearby. This was a small museum but well worth stopping by for an hour; it's also right next to the cathedral and it's an easy walk over to see on the same trip.

Next I had to drive from Salisbury to my last major destination of the day, the nearby small city of Winchester. These two cities were located about 25 miles / 40 kilometers apart and, unlike the drive from Avesbury, I was able to stay on major roads the whole way for this trip. I found an underground parking garage beneath a shopping mall in the central part of Winchester, then had to squeeze into this absurdly narrow parking spot since the place was pretty packed. I couldn't even open the front door and had to get out through the rear door. Unfortunately I had scraped up against a road barrier when exiting downtown Bristol earlier that morning, and the second picture from a different day of driving captured the damage that had been done. This white rental car picked up some of the blue paint from the barrier along with a series of small dents in the passenger side door. I'm a pretty good driver but between the need to drive on the opposite side of the road and navigate England's ridiculously narrow road conditions, it wasn't surprising that the rental car took a few bumps and scrapes along the way.

Anyway, driving mishaps aside, now I was visiting Winchester which is another location that would have been far more famous to medieval travelers than modern ones. Winchester is a small city today, comparable to Salisbury with just under 50,000 people living in the area. It's been inhabited since ancient times, first as a hill fort in the Celtic period under a name something like Wenta or Venta, then as a Roman town known as Venta Belgarum, then controlled by Anglo-Saxon arrivals during the early medieval period and redubbed as Wintanceaster, which eventually became Winchester in modern English. This was the capital of the Anglo Saxon kingdom of Wessex during the time of Alfred the Great, though that didn't have the same meaning in the 9th century as the ruling court tended to move from place to place. These were pictures of some of the pedestrian walkways in the center of Winchester near High Street, which sloped gently down towards the Itchen River. The big Winchester Guildhall looked like a medieval building but was not, instead dating from the 1870s and built in Gothic Revival style. There was also a statue of Albert the Great here dating from 1901, which may or may not have looked anything like the actual king of Wessex.

I had started out my visit to Winchester by walking through the shopping area down to the statue of King Alfred. I turned to the south from there and walked through a small park named the Abbey Gardens, a pleasant little patch of greenery flanked by a series of very old looking stone walls. Winchester was originally walled for protection and this is the only part of the city where those walls are still standing. A little bit to the southwest was one of the few surviving gates in that wall known as the Kingsgate. This opening in the walls probably dates back to the 14th century and it still appeared to be in good condition; there was even a bookstore called Kingsgate Books and Prints located inside the wall itself. It's probably worth mentioning here that Winchester has a highly affluent population and this city is frequently rated as one of the best places to live in Britain. It's a very nice and very expensive small city.

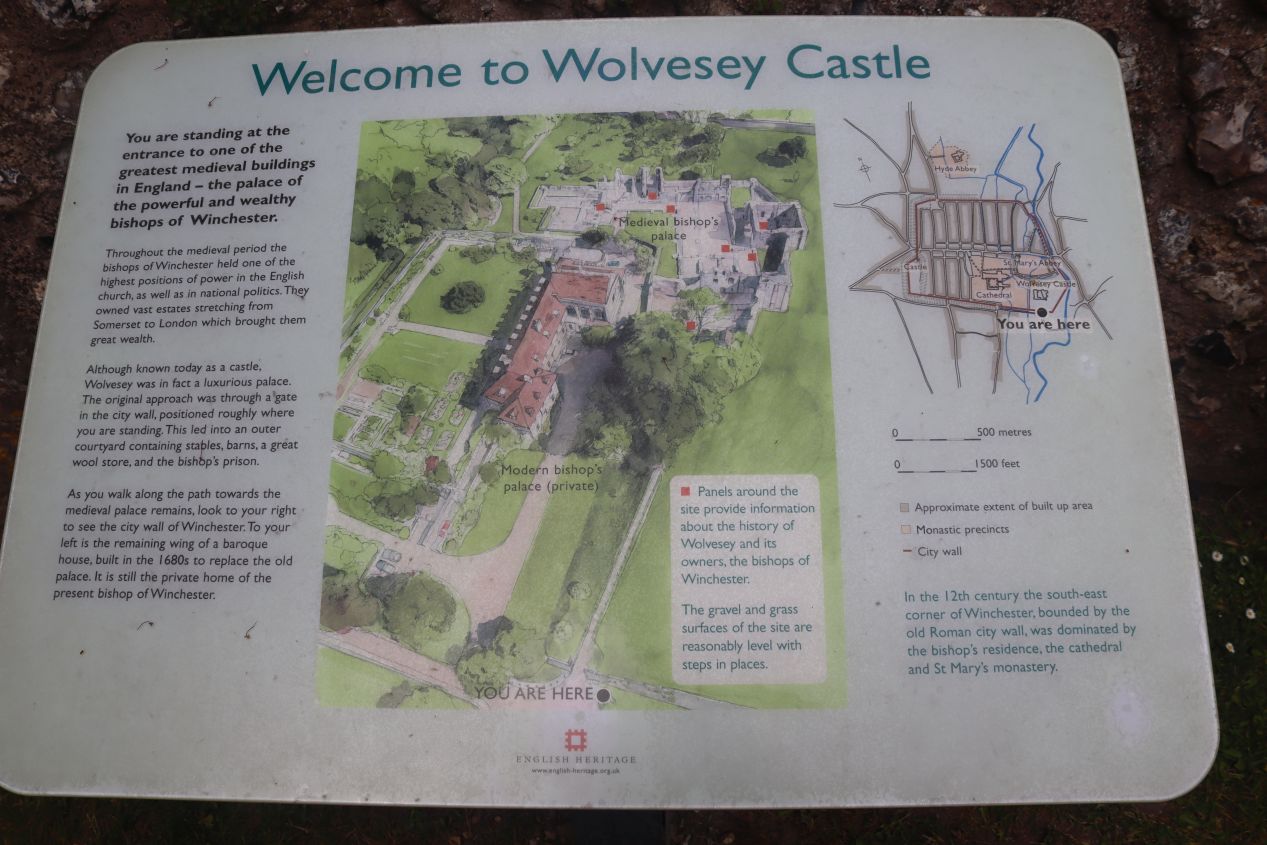

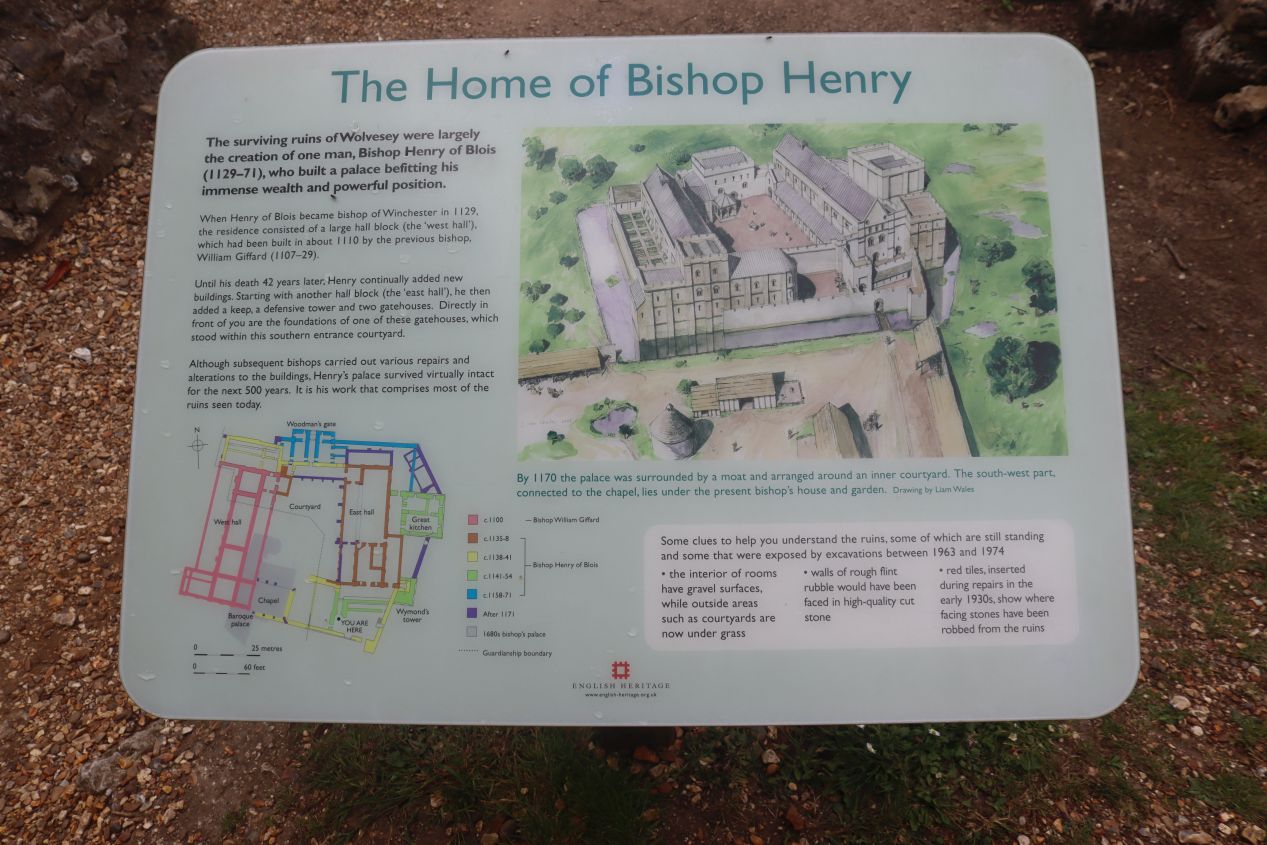

On that note, the small road on the other side of the Kingsgate led me past Winchester College. This is an elite boarding school for the families of the well-to-do, one of the public schools (i.e. private schools) that are so well known in England. I passed by some of the students playing a mixture of cricket and soccer/football in a grassy field nearby which looked like it would have been fun. What I didn't realize at the time was that I actually captured some of the very few surviving remains of the city's Roman walls in the background of that picture. I wish that I could spend more time playing sports next to a wall that's nearly 2000 years old. This field was also situated next to Wolvesey Castle (the reason why I had walked down here), which was a medieval castle housing not a secular lord but rather the Bishops of Winchester. I mentioned before that this was a cathedral city and the Bishops of Winchester were powerful and influential figures throughout the medieval period. The modern bishop's residence dates from the 1680s and is not open to the public while the original medieval palace lies in ruins today:

These stone foundations are all that remains of the palace built by Bishop Henry of Blois over the course of the 12th century. Bishop Henry was the brother of Stephen of Blois, the upstart king who seized the throne following the death of Henry I in 1135 and helped to touch off two decades of civil war known to historians as the Anarchy. Henry certainly was not averse to using his status as one of the highest-ranking churchmen to enrich himself, as he built this huge palace over the course of four decades and repeatedly played a major role in the shifting political currents of mid-12th century England. This might seem strange to modern visitors but the medieval church was incredibly wealthy and owned a tremendous amount of land across pre-Reformation England. The fact that the Bishops of Winchester had their own palace wouldn't have been surprising to medieval visitors.

Modern visitors to Wolvesey Castle can stroll around the ruins without needing to pay an entry fee. Given the fact that most of these ruins are approaching 900 years in age, they've been preserved in excellent shape and it's still possible to see the outlines of the original structures. A series of information signs help explain the purpose of each building and how they were fortified for protection during the Anarchy. It's a bit of a walk to get down here from Winchester Cathedral proper but very much worth the time investment; if nothing else, it helps provides context for why so many people were ready to rebel against the church's authority a few centuries later during the Reformation.

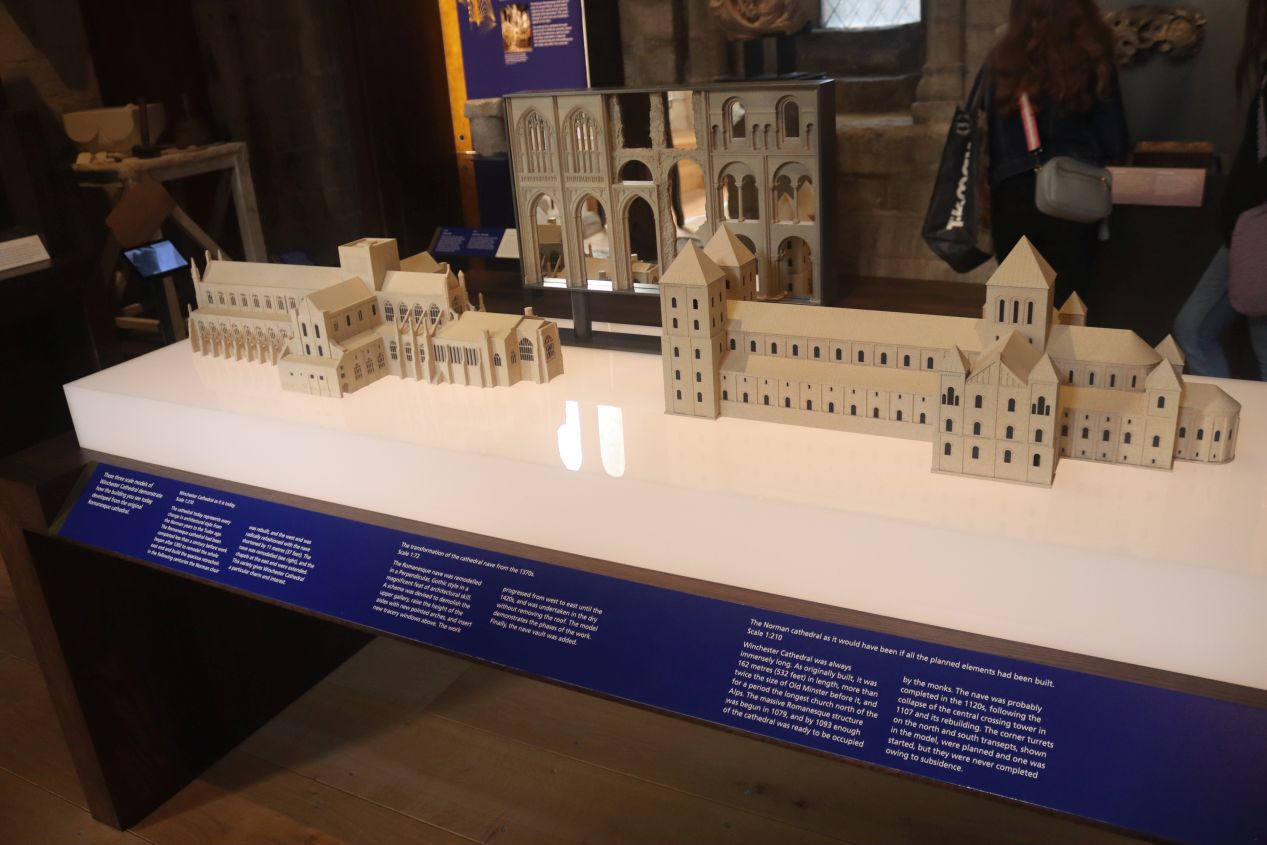

I walked back from Wolvesey Castle until reaching Winchester Cathedral itself, arriving from the south and then walking around to the main entrance on the western side of the building. Winchester Cathedral lacks the height of Salisbury Cathedral but makes up for it in length: stretching out to an extent of 170 meters / 558 feet, this is the longest medieval cathedral in the whole world. I mentioned above how Salisbury Cathedral was unusual in having been almost entirely completed in a span of three decades. Winchester Cathedral was more typical as its construction stretched over a process of centuries, beginning in 1079 and not completely finishing until 1532. This resulted in Winchester Cathedral having a mixture of different architectural styles as the oldest core dating to the Norman period was added onto and replaced in parts over many following generations. There were only a handful of people visiting the cathedral on this afternoon and I would largely have the place to myself over the next hour.

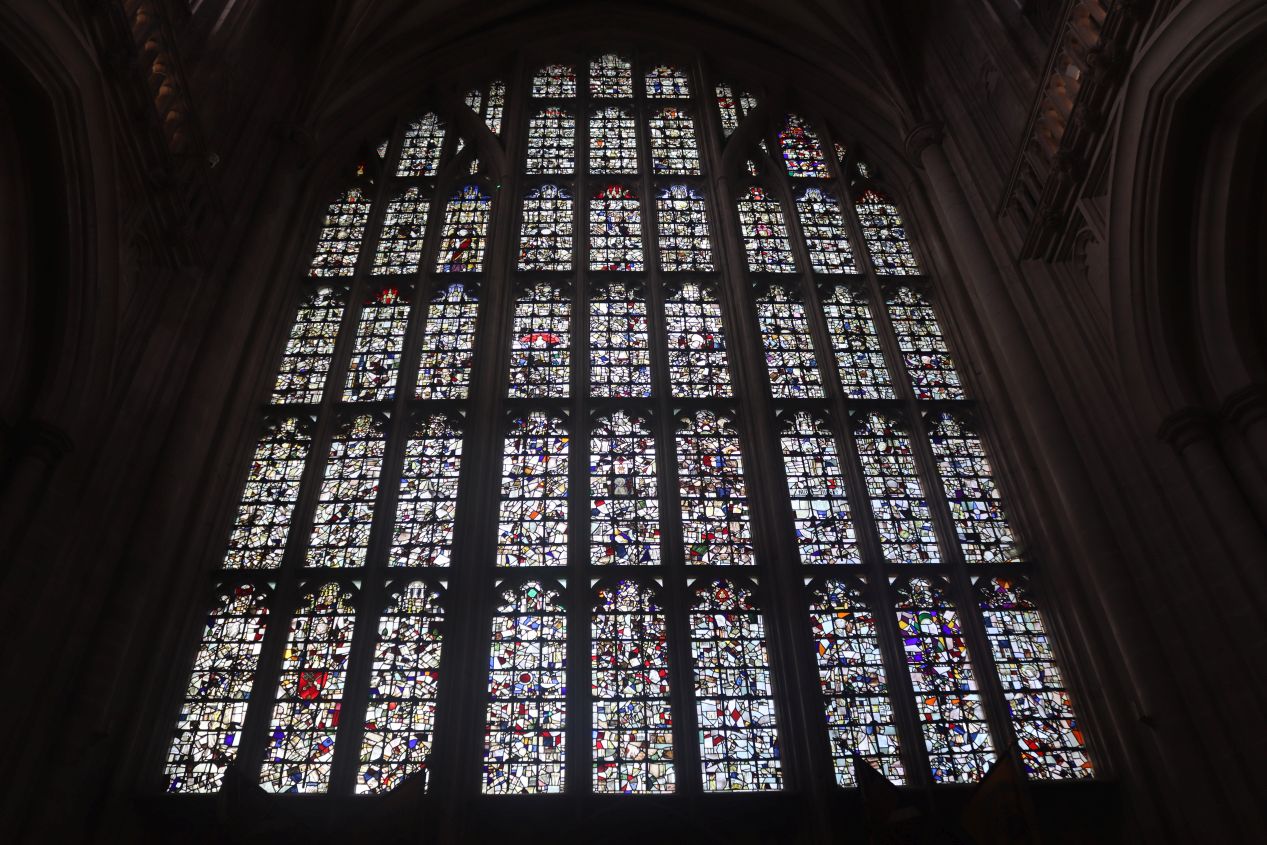

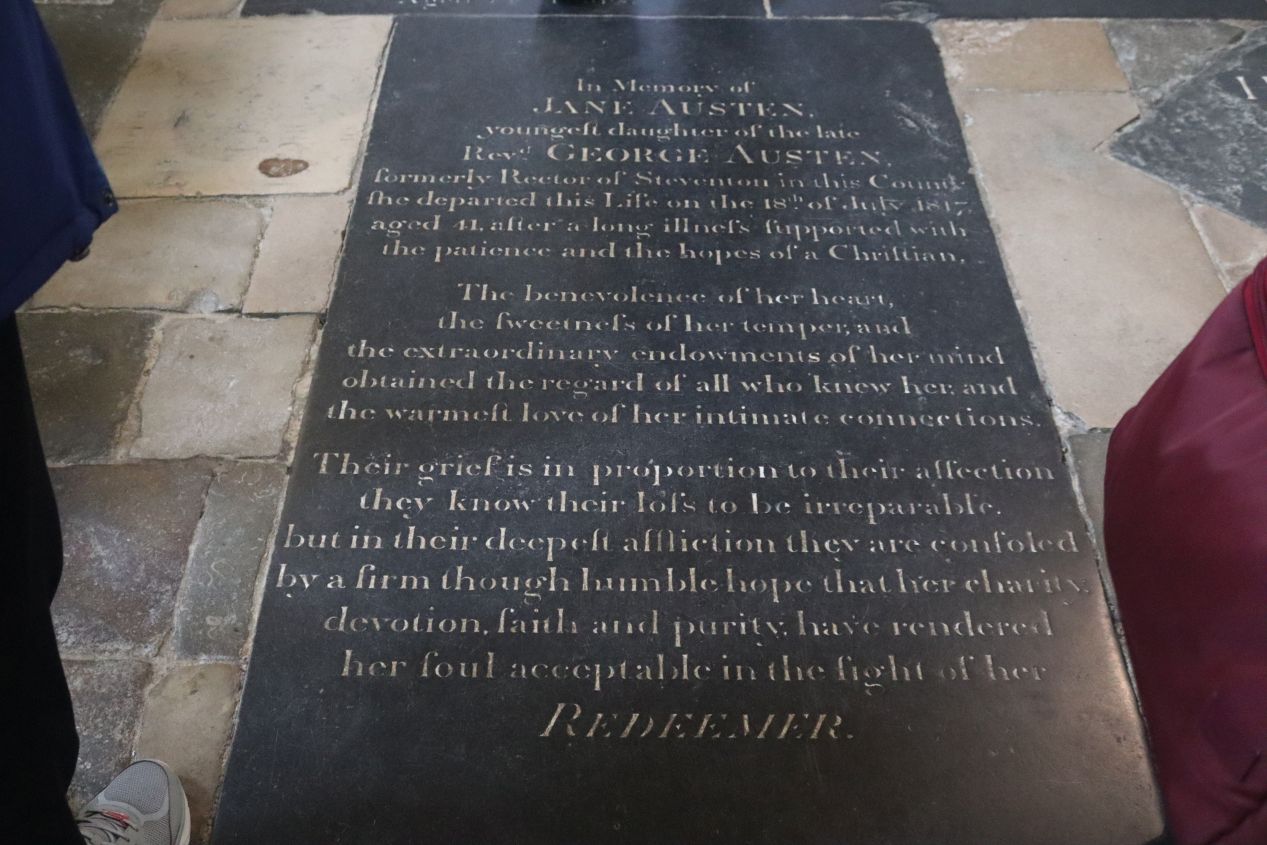

This was the interior of the cathedral as seen from the entrance on the western side. This part had the standard Gothic design and didn't look much different from Salisbury Cathedral, due to the fact that this section was constructed in the mid-14th century by which point in time the Gothic stylings had become commonplace across western Europe. The stained glass on the magnificent Great West Window unfortunately did not survive from the medieval period; it was smashed apart by overzealous Puritans during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the 17th century and then replaced with clear glass after the monarchy's restoration. A more recent addition to the cathedral was the gravestone of Jane Austen who was buried here in 1817. Apparently this is one of the biggest reasons why people come to the cathedral and I hadn't even known that she was buried here. I likely would have missed the gravestone entirely if a tour guide hadn't been discussing the topic as I passed by.

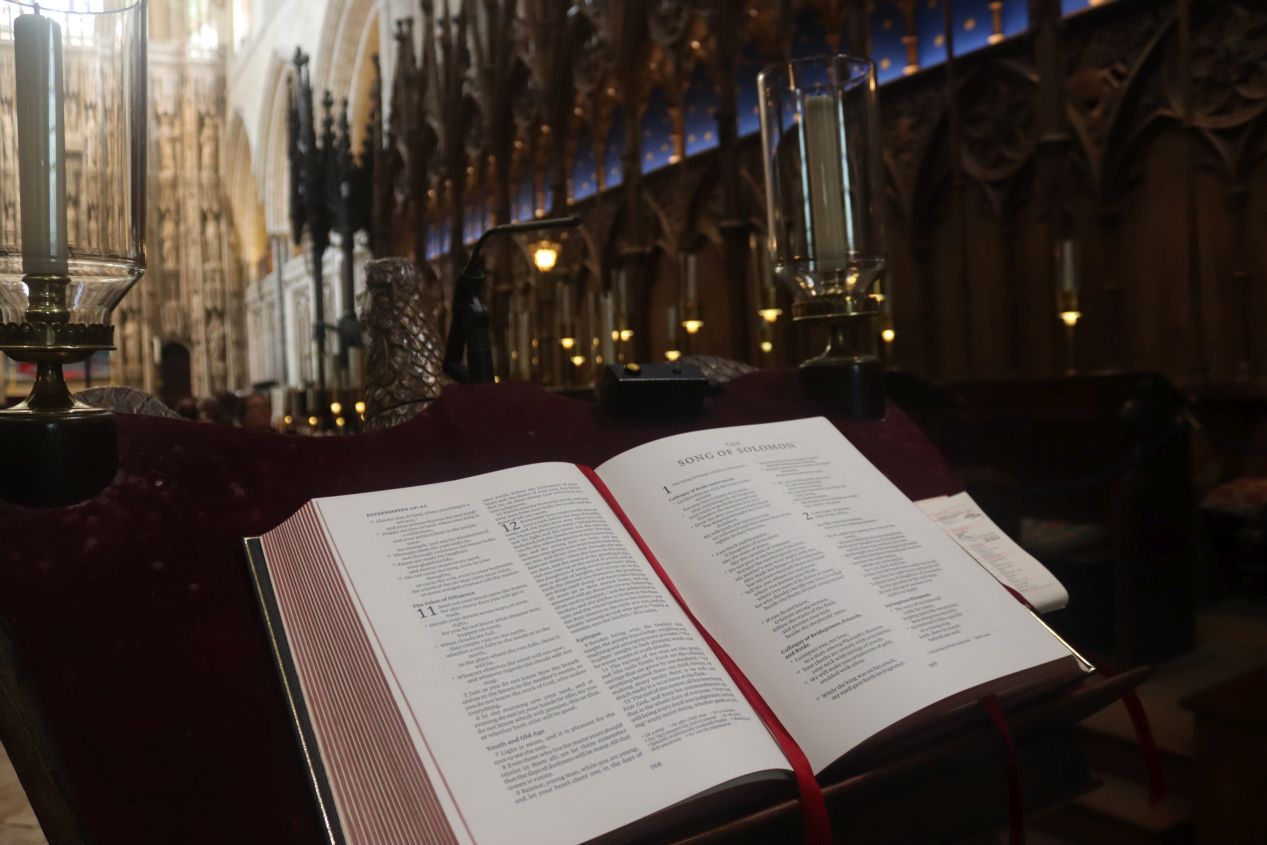

As I continued onwards into the center of the cathedral, I came across the main altar followed by the choir area behind it. While the altar was certainly nice enough, it was the beautiful choir section that once again drew my attention as it had at Salisbury Cathedral earlier. There were a series of wooden benches here with small (electric) candles to light the notes on sheet music, then a bright blue pattern decorated with golden stars along the walls to add a splash of color in the midst of all that wood. Along with the high vaulted ceiling overhead carved from white building stones, this was the prettiest part of the cathedral as far as I was concerned.

At the back end of the choir was another altar placed in front of something called a reredos. This is a type of large decorative screen placed behind an altar, usually depicting religious iconography, and the one at Winchester Cathedral is known as the Great Screen. It was carved from stone and dates from 1450-1476 towards the end of the cathedral's construction. The attention to detail on the carvings was incredible although it did give this part of the cathedral a very heavy feeling for lack of a better word. There was also a tomb here containing the remains of Bishop Henry of Blois, the very same individual who had built Wolvesey Castle that I had just visited half an hour earlier. King William II of England (William Rufus) was also buried here previously in 1100 before his remains were moved at a more recent date.

These pictures were taken over at the north transept (one of the side wings of the cathedral), and it was clear even to a non-architect like me that this was one of the oldest parts of the cathedral. The transepts are one of the few areas that date back to the Norman period and they had a rougher, less finished aspect to them as compared to some of the later parts of the cathedral. The faded paintings on the walls here dated back to the 12th century and depicted the burial of Christ after the crucifixion. Then there was a staircase leading down to the cathedral's Crypt which has also remained unchanged since the Norman period. There's a statue here named "Sound II" by Antony Gormley which was added in 1986 for reasons I haven't been able to determine. The crypt frequently floods and there was a little bit of water here at the time of my visit; this whole area was blocked off to visitors since it wouldn't be safe for tourists to walk around down there.

There's also a remarkable story involving this flooding of the cathedral and the superhuman efforts required to keep the building from collapsing. The medieval builders unknowingly constructed Winchester Cathedral on soft ground and by the beginning of the 20th century the whole structure was on the point of falling. There were huge cracks forming in the walls, the cathedral was beginning to lean, and stones were falling off on a regular basis. When engineers attempted to shore up the building from underneath, they ran into the problem of water flooding into the trenches that they dug, water that couldn't be pumped out without the whole building collapsing. The solution was to turn to an experienced diver named William Walker: he had the job of descending into the pitch-black flooded trenches in a primitive early 20th century diving suit and then lay bags of cement to plug the water coming up from below. Walker worked 6 to 7 hour shifts almost every day for six years to achieve this, after which the water could be removed and the foundation of the cathedral stabilized. Walker's heroic efforts saved the cathedral from destruction and ensured that future generations would be able to enjoy this medieval treasure.

These pictures were taken at the eastern end of the cathedral, at the point furthest from the main entrance and behind the altars in the nave of the church. This section is known as the Lady Chapel and it was constructed in the middle of the cathedral's history between 1202 and 1220 in Early English Gothic style. There was a shrine here to Saint Swithun who was Bishop of Winchester from 852 to 862; the Anglo-Saxon name "Swithun" itself indicated how long ago this saint lived. Unfortunately for poor Saint Swithun, his remains were destroyed in 1538 during the dissolution of the monasteries across England. There were a number of other funerary chests here as well, visible at the top of the fourth picture far above walking height. A number of kings of Wessex are supposedly held in those chests, kings with names like Ethelwulf and Eadwig and the like. King Canute of England and his son Harthacanute are both here as well, though whether any of these chests actually hold the remains of these historical personages is a matter of debate. Alfred the Great was originally here but was moved a few blocks north to Hyde Abbey in 1110, then his remains were driven underground during the dissolution of the monsteries, then some convicts working on a building project accidentally dug up the coffin in 1788 and destroyed its contents. Thus there's nothing left of Alfred's remains today although the former site of Hyde Abbey has a commemorative display at the site where they used to rest.

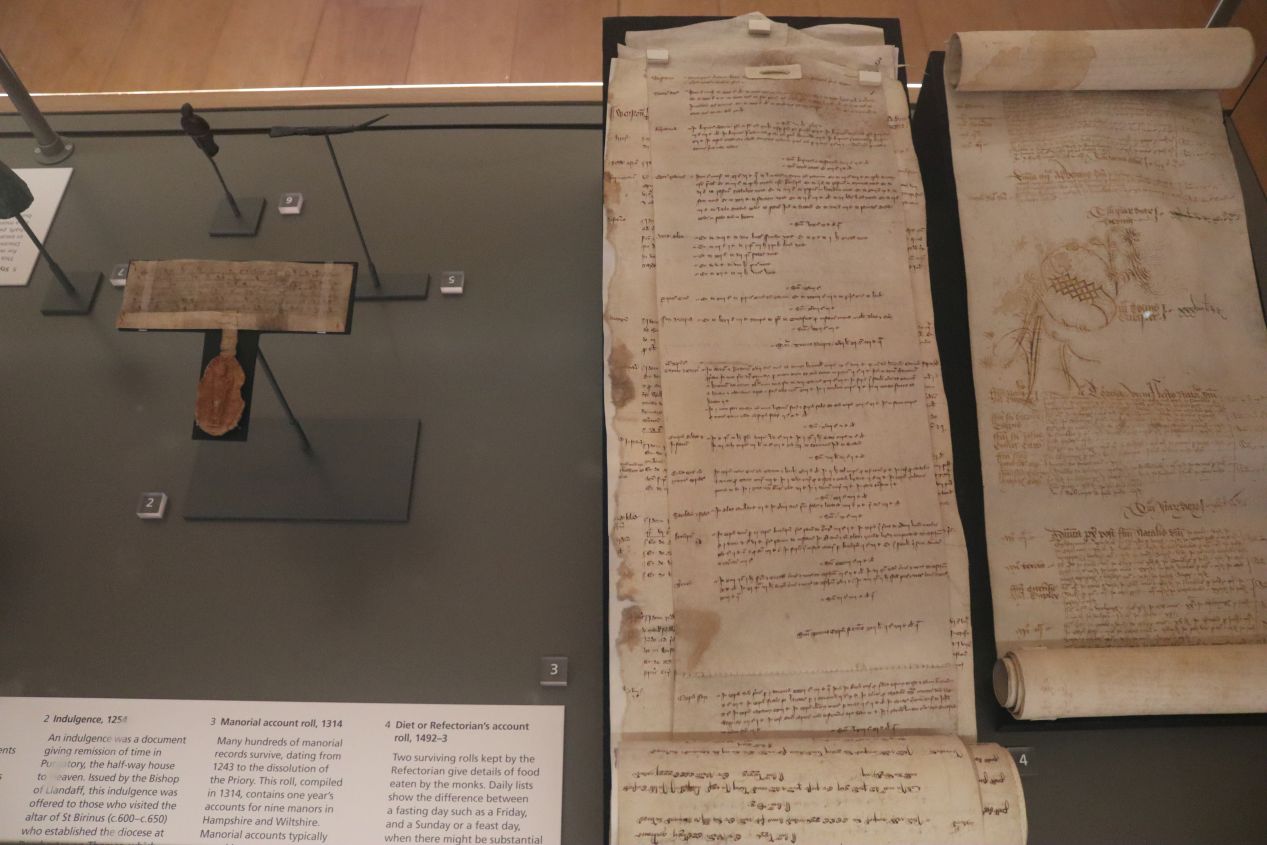

The south transept of the cathedral was the other old Norman part of the building. Unlike the north transept, however, this part had been transformed into a small museum within the cathedral showcasing some of the artifacts in its collections. There were a number of documents from the medieval period on display, various ledgers and indulgences written by the monks who had lived in the monastery attached to the cathedral before it was destroyed by Henry VIII's edict. Most famously, the cathedral also had the Winchester Bible for visitors to see, which is considered to be the largest and best-preserved 12th-century Bible in England. (This was the one document that tourists were understandably not allowed to photograph.) Up a flight of stairs was a large collection of books known as the Morley Library, an assortment of rare books given to the cathedral by George Morley who was Bishop of Winchester from 1662 to 1684. Even the shelving that the books sat on dates back to the 17th century. Visitors were not allowed to touch the books but the guide sitting outside the library said it was OK for me to take a picture as long as I didn't use a flash.

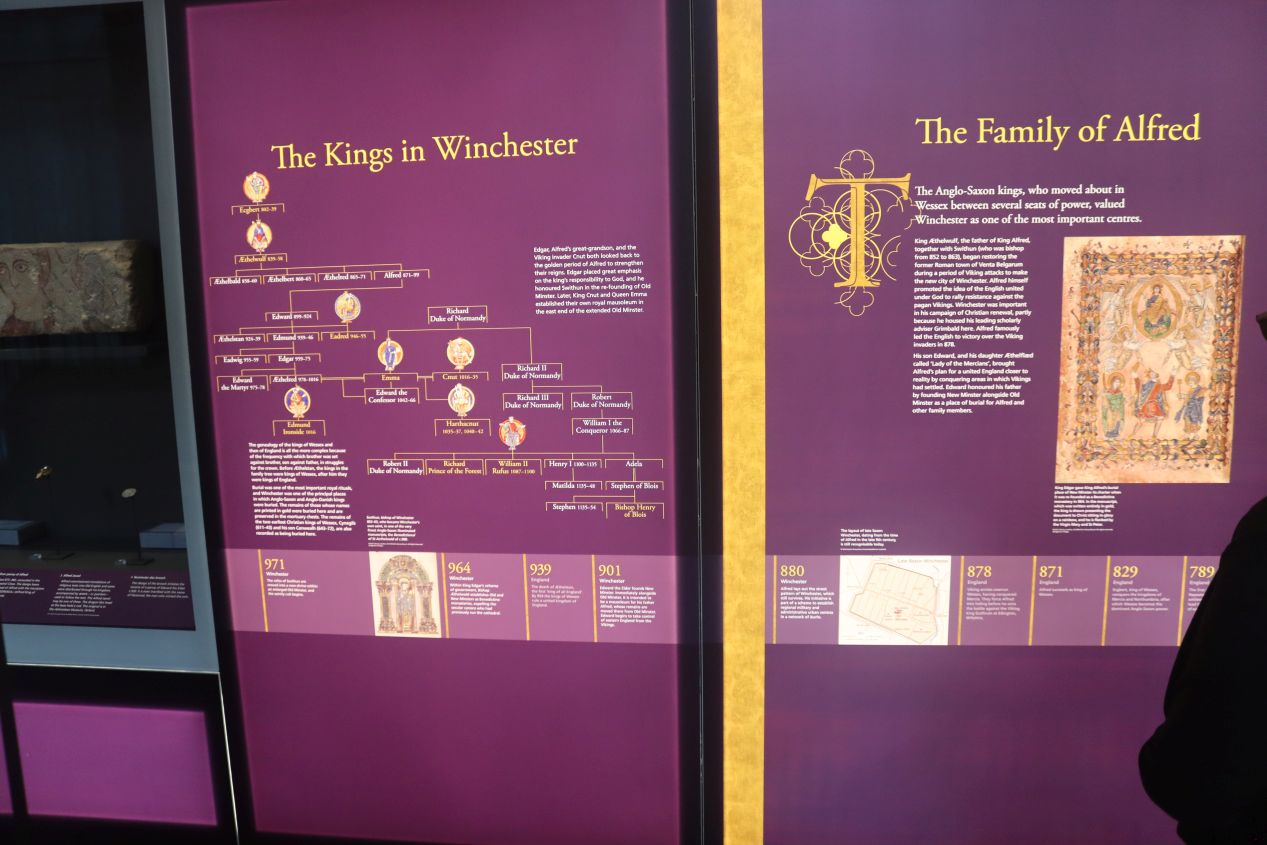

There were three floors in all comprising this exhibition known as "Kings and Scribes", with the top floor looking the most like a typical museum display (aside from being in the middle of a cathedral!) The small museum had a lot of information about the Kingdom of Wessex and its ruling family during the Anglo-Saxon period, then traced the history of the cathedral over the course of its many centuries. I liked the models of the cathedral showing how it was originally conceived by its Norman builders as compared to the much more Gothic design that it ended up with. There was also a lot about the necessary preservation work that has taken place to protect the cathedral as well as the many threats that it faced over the years, from Henry VIII to extremist Puritans to simple vandals. I really enjoyed this little exhibit and the fact that it took place in such historic surroundings only made it that much more fun to experience.

Time was running out on this day as I still had to drive back to Bristol to meet Liz for dinner, however I did make one final stop before departing Winchester. This was the Great Hall of Winchester Castle, located a few blocks west of Winchester Cathedral and dating back to the 12th century. The Great Hall is a large open space originally used to host banquets and other pagentry, best known today for including King Arthur's Round Table, which has hung in the hall since at least 1463. While it was popularly believed to be the real Round Table of King Arthur, the table actually dates from the 13th century and still remains historically significant for that reason alone. King Henry III was born at Winchester Castle and the Great Hall was constructed early in his reign, though the rest of the castle no longer survives to the present since it was demolished by Oliver Cromwell in 1649. I arrived at the Great Hall late in the afternoon just as this school group was entering, and I think the staff mistakenly believed I was with the student group since they didn't ask me for an admission fee. I didn't bother to correct them because the truth was that there wasn't much to see here. The Great Hall and the Round Table were pretty neat but almost certainly not worth the admission price. This attraction is probably skippable for anyone short on time.

Afterwards, I made my way back to the parking garagae with my rental car and drove back to Bristol, arriving about a half hour late because I had to fight my way through rush hour traffic. It was a great day of sightseeing despite the driving mishaps and I truly enjoyed having the chance to see these cathedral cities along with the tiny hamlet of Avebury. The fact that Winchester was the seat of government for the Kingdom of Wessex might not mean anything to most people but it certainly did for a British history Ph.D. Next up I would be taking my biggest excursion of this trip: driving down to Cornwall and then back again to experience one of the most remote of England's counties. It was going to be a tough but rewarding travel day; details of that excursion follow on the next page.