"A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away."

- Antoine de Saint-Exupery

In June of 2015, an announcement appeared out of the blue stating that a new version of Master of Orion was under development. To say that this came as a surprise was an understatement. Master of Orion had been dead and gone for over a decade, with the bloated and putrified corpse of MOO3's disastrous 2003 release scaring everyone away for long years on end. (I don't want to beat a dead horse here, so I'll simply state that MOO3 is the single worst empire-building strategy game that I've ever played. It was a disgrace to the Master of Orion name in every sense of the word.) However, just as Hollywood can't stop reviving and sequelizing even the most marginal properties from the past, gaming publishers are also always looking to exploit brand name recognition from earlier days. Thus we have the new Master of Orion reboot (which I'll call MOO 2016); the IP rights to MOO were snapped up by the publisher called Wargaming, best known for creating the World of Tanks online PvP game. The actual development will be handled by an Argentinian company called NGD, a virtual unknown who has never worked on a strategy game previously. These are two strange groups to be helming the MOO reboot, and not exactly entities to inspire much confidence.

What do we know so far about MOO 2016? Based on reading through the early media coverage, the developers have been stressing two things. The first one is the low-hanging fruit of improved graphics, with the easy-to-please gaming media gushing about how pretty the Mrrshans and the Alkari look in HD. Don't get me wrong, I'd enjoy seeing a modern version of all the old MOO faces as well, but this is a relatively minor issue for a strategy game, and pre-release screenshots are notoriously unreliable. The second item of emphasis from the developers has been the nostalgia angle, as the memories of older gamers have been shamelessly exploited in the gaming media thus far. Look, all ten of the original races are coming back again! And now they're being voice-acted, wow! Look at how cool the spaceships are in HD! Who remembers fighting the Guardian to reach the planet Orion? That's supposed to be back too! Come and re-live your childhood all over again!

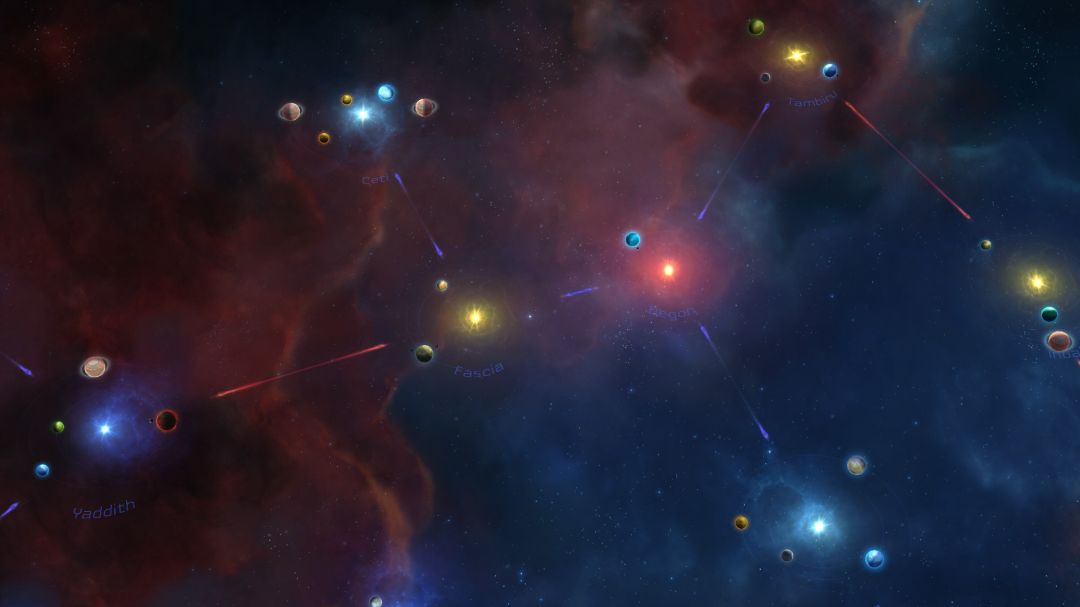

All kidding aside though, there's a serious question to be asked here. Do the developers of MOO 2016 actually understand what made Master of Orion so brilliant in an attempt to recapture that spirit? Or did Wargaming simply purchase a famous name to be slapped onto a generic modern empire-builder set in space? I can't be the only one troubled by the headline on one of those previews that states "A PC Gaming Classic Dragged Into the Modern Era." Is that what fans of Master of Orion really want to see? Reading between the lines of the developer interviews has not been encouraging thus far. The few details that have been given about the game's economic system suggest that it will be based on Master of Orion 2, which would be a poor choice if true. MOO2's planetary setup was heavily based on micromanagement (it actually used the same system from Master of Magic, not Master of Orion) and lost the far superior sliders from the original game. There have been few details released as yet about combat or ship design. As for the galactic map... WTF are those things?!

Yep, the dreaded starlanes from Master of Orion 3 are making a return.  No details on how they will be implemented, but forcing movement from system to system into narrow paths is never a good sign. Elsewhere, the tech tree has been described as "an immense branching tree" with hundreds of techs. The developers have described diplomacy as taking place on a Civilization-esque leaderhead screen, with opportunities for treaties, tech sharing, resource trades, and the like. There are going to be five different victory conditions: conquest, technology, diplomacy, economics, and "excellence", whatever the heck that is!

No details on how they will be implemented, but forcing movement from system to system into narrow paths is never a good sign. Elsewhere, the tech tree has been described as "an immense branching tree" with hundreds of techs. The developers have described diplomacy as taking place on a Civilization-esque leaderhead screen, with opportunities for treaties, tech sharing, resource trades, and the like. There are going to be five different victory conditions: conquest, technology, diplomacy, economics, and "excellence", whatever the heck that is!

All of that sounds well and good right? Yes - if your goal is to make the next Galactic Civ or Endless Space game. But this isn't Galactic Civ, it's Master of Orion, and that right there is the problem. Everything that I've read to date suggests that the developers are making a generic space strategy game. None of these mechanics reflect the genius of the original MOO at all. At the moment, this looks like Galactic Civ 4 with a less-talented publisher and development team backing it. After all, just having the Master of Orion name on the cover doesn't make this a true Master of Orion game. A real sequel would need to have the simple planetary slider controls, the variable tech tree, the brilliant racial traits design, the diplomatic system with "enemy of my enemy" gameplay and limited trading opportunities, the defensive-based combat system with those upgradable missile bases... Look, it's not happening. Not in this reboot, and probably not ever again.

This article isn't an attempt to bash the designers of MOO 2016. I'm sure they're doing the best they can, and it's possible that they might turn out a good game. (I'm not optimistic.) What I want to do here is first explain what makes Master of Orion such a masterpiece of game design. Sirian has written about this a great deal on his website, but mostly in bits and pieces of different reports, not collected into one place. I'm going to add my thoughts on this subject with a decade of experience playing MOO behind me, and then finish by explaining why we'll never see another Master of Orion-type game again. Unfortunately the same things that make Master of Orion a classic are the same things that prevent it from being duplicated in the current gaming environment.

In a nutshell, it's the game's simplicity.

Master of Orion looks like a very complex game on the surface. The planetary management scree has those five sliders that can be locked and dragged around, which are certainly not as intuitive as moving a worker in Civilization and telling him to build a farm. The galactic map talks about parsecs and hostile environments and "Artifacts" worlds and so on. The technologies sound extremely intimidating at first, with mentions of Improved Robotic Controls and Controlled Dead Environment and Reduced Waste 60% and other gibberish. The ship building screen asks the player to decide whether to add levels of computers, ECM, armor, shielding, specials, and as many as four different weapon types. Systems like Reserve spending and Espionage are not explained anywhere in-game with tooltip help. (Of course there's a reason for this; MOO was designed in 1993 and intended to be sold with a printed instruction booklet. The out-of-game documentation for MOO was outstanding and did explain the mechanics in great detail.) When it comes to first impressions, Master of Orion looks like an impenetrable wall of science fiction mumbo jumbo layered over extremely complicated gameplay mechanics.

However, appearances can be deceiving. These first impressions are in fact not the case at all. While Master of Orion might look like a complex game, the mechanics are actually the simplest out of any game in the genre that I've ever played. That includes the original Civilization from 1991, which had many mechanics that went completely unexplained and made no sense in context with one another. (My favorite one being how Democracy government in Civ1 had zero corruption - LOL!  - and don't get me started on the abuses possible with diplomats and proper use of We Love The King Day.) Master of Orion is almost brutal in the way it strips out everything other than the core gameplay systems needed for a strategy game. Let me highlight a couple of the main mechanics to provide some examples of how this works in practice. I'll try to use a few comparisons with similar systems in Civ4, another outstanding empire-building game near and dear to my heart. Civ4 looks on the surface like a simpler game, due to the familiarity of the historical setting, but it actually has far more complexity than MOO. And I don't necessarily mean that as a compliment.

- and don't get me started on the abuses possible with diplomats and proper use of We Love The King Day.) Master of Orion is almost brutal in the way it strips out everything other than the core gameplay systems needed for a strategy game. Let me highlight a couple of the main mechanics to provide some examples of how this works in practice. I'll try to use a few comparisons with similar systems in Civ4, another outstanding empire-building game near and dear to my heart. Civ4 looks on the surface like a simpler game, due to the familiarity of the historical setting, but it actually has far more complexity than MOO. And I don't necessarily mean that as a compliment.

I'll begin with something easy: the map. Master of Orion is obviously set in space, and the different planet types (Terran, Arid, Barren, Inferno, etc.) are not immediately intuitive to a new player. There is a learning curve associated with understanding what these things mean, and how to research technology to unlock the hostile environments. After a short while, however, the lightbulb will go off in the player's head and suddenly everything starts to make sense. Habitability type lets you know what can be colonized and what can't, and it's easy to see right on the map screen the different levels of hostility. Planet size is just how many people can fit on each world; more is always better. Rich and Poor planets are easy to understand, they get bonuses or penalties to industry. Your population grows faster on Fertile worlds and slower on Hostile worlds. Distance between systems is measured in parsecs, and your ships will move their warp rating in parsecs each turn. And... that's basically it. There's nothing more to learn. What looks confusing at first turns out to be simple in practice.

The planetary economy functions in the same way. Each planet will spend its entire income every turn, in a formula that's relatively simple to understand. (1 BC per factory worked and 0.5 BC per population at the start of the game.) That income gets divided between the five sliders as set by the player. You need to spend a certain amount of income to clean up pollution, but the rest can be allocated in any way that the player desires. Click to lock a slider, click again to unlock the slider. Income can be moved easily between shipbuilding, missile bases, factories, population growth, or research. All of the planetary upgrades are handled on the same screen as well, from terraforming to upgrading missile bases to building stargates. While the exact formulas involving factory controls and terraforming can be a bit tricky, the basic mechanics truly are simple. Once the player gets over the initial sense of confusion, at some point it all starts to click together, and afterwards colony management is smooth and easy. The game even keeps track of overflow, rolling over anything extra beyond what's needed for the current project into the Planetary Reserve. Furthermore, all of the planetary management takes place right on the galactic map itself, with no need to open up a separate screen. It's honestly kind of amazing how an ancient game like MOO can have an interface so far superior to something like Galactic Civ 3, which requires many mouse clicks and digging into subscreens to get anything done. Master of Orion has the least micromanagement of any empire-building game I've ever played, all thanks to those lovely sliders.

Now compare that to what takes place in a game of Civ4. The map certainly looks less intimidating at first, showing a bunch of real world terrain instead of the vastness of space. But the Civilization mechanics get complicated in a real hurry. There are well over a dozen types of basic terrain in Civ4: grassland, plains, desert, tundra, ice, hills, forests, jungles, mountains, floodplains, river versus no river, oasis, coast, ocean, and so on. Then there are the resources to consider; Civ4 has three different types divided into health (corn, cows, fish) and luxuries (gems, dyes, wines) and strategic resources (iron, horses, coal, oil). Different resources can appear on different terrain types to modify the tile yields. Resources are also improved by researching different technologies; Civ's aided in this because of the historical setting, but just think how complicated it is to remember that you need to research Bronze Working to connect copper and gold resources, Calendar to connect bananas and spices, Monarchy to connect wines, Optics to connect whales, and so on. Then there are the workers themselves, which can build another two dozen different tile improvements: farms, mines, cottages (which transform over time into hamlets and towns!), workshops, windmills, watermills, lumbermills, forest preserves, plantations, oil wells, roads, railroads, etc. All of these improvements are associated with their own techs, not always in an intuitive manner. Furthermore, tile improvement benefits can be increased by researching OTHER technologies, such as how windmills are improved by Electricity, and improvements can also be altered by certain civics, like Caste System empowered workshops or State Property buffed watermills. What looks simple turns out to be a very complicated and confusing system.

And those are just the tiles on the map itself. Then there's the management of the cities in Civ4, which can construct all manner of different buildings, projects, and wonders. Master of Orion's planets typically have three things to track: population, factories, and missile bases. That's essentially it; you could also include any built up pollution, the level of planetary shielding, and the presence or lack of a stargate to be technical, but even that only gets up to six total items. By contrast, a city in Civ4 can construct almost TWO HUNDRED different buildings of some sort, each with their own unique characteristics. Even if we just stick to wealth generation, there are markets and grocers and banks, plus the national wonder that increases gold (Wall Street), plus the unique building replacements that individual civs have (like the forum and the stock exchange). These buildings also have secondary functions too, with markets providing happiness and grocers providing health (but only with certain resources! Gotta remember that markets get the happiness bonus from ivory but not from wines!) And that's limiting our discussion only to the wealth generating buildings. There are dozens and dozens more dealing with research, production, culture, city defense, unit experience, health/happiness bonuses, additional trade routes, etc. Plus there are the religious buildings (which come in seven different types for each religion), then all of the national wonders (each with its own requirement for construction), then the world wonders, and then the special endgame projects like the spaceship parts. Every one of these things is associated with its own tech, and in order to play Civ4 at a high level, it's necessary to memorize where all of them are located on the tree, what all of them do, and how they fit together into a bigger whole. While Civ4 is an amazing game in its own right, my goodness is there a lot of complexity to wade through!

I'll use one more example here: the research system itself. Civ4 has the best designed tech tree of any empire-building game that I've played. It presents tough choices at nearly every stage of the game from beginning to end, and no two games ever play out in exactly the same fashion. The fact that there are six different starting techs (each civ gets two of those six) is absolutely brilliant, and that combined with the randomness of the local terrain makes for innumerable different opening research paths. Why Civ5 dropped this and went back to the same old "everyone starts with the same tech" setup is completely baffling to me. Civ4's tech tree also is completely open-ended; while there are a handful of cross-tree requirements, it's possible to dive very deeply into certain parts of the tree, and ignore other parts entirely. As I've written before, it's perfectly possible to launch the spaceship without researching a single religious tech. The monk parts of the tree are all optional in Civ4.

So Civ4's tech tree is more or less the best that can be done with a linear setup. There are two flaws inherent in this design, however: complexity and rigidity. The complexity problem is one that can only be overcome with lots of time and experience, as Civ4's tech tree is immensely complicated and overwhelming to newcomers. There's no way around the need to memorize what all of the techs do, since each one of the 85 techs is completely unique. The historical setting of the game helps (it's easy to intuit that Writing lets you build libraries for example), but there's still a ton of information to digest. The second design problem is the inherent weakness of a linear tech tree: it always stays the same. I think this is probably mandatory for the Civilization series, as a game modeling history needs to unfold in a roughly accurate way. Nevertheless, any static system can be metagamed with enough time, and as good as the Civ4 tech tree may be, there are certain power paths that tend to be followed (such as the infamous Liberalism into Nationalism play). It's a testament to the excellence of Civ4's tech tree that our Multiplayer games still see quite a bit of diversity in the tech path, rather than having One Right Choice (TM) in every contest.

Master of Orion has a unique technology system that no other empire-building game has ever adopted. (As Sirian wrote years ago, I don't understand why someone else hasn't simply copied this setup root and branch.) Master of Orion has a system that I envision as being more like a tech ladder; techs are grouped together into rungs, and the player must research (or trade or steal) one tech in each rung to move on to the next one. You can research more than one tech at each rung or push on to the next rung as fast as possible. The genius of MOO is that the tech tree CHANGES from game to game; each tech only has a 50% chance of appearing in your tree. Sometimes all options within a rung will be there, sometimes there will only be one of them, and the player will have no choice what to research. (You are always guaranteed of having at least one tech per rung.) Furthermore, you can't see what techs are located at the next rung ahead of time, and you can't change your research once a tech has been started. This forces some very difficult decisions on the part of the player. It's a great example of the core philosophy behind Master of Orion's design: the gameplay is improved by taking options AWAY from the player. This is an extremely important point, and we'll come back to this later in the article.

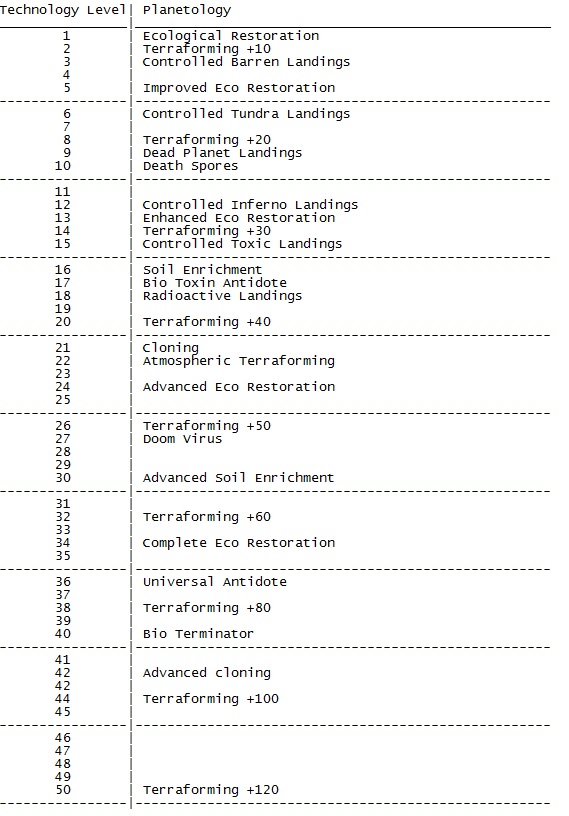

Master of Orion is able to have this tech setup with variable parts on each rung of the ladder due to the simplicity of the techs themselves. Although there are roughly 150 techs in total present in the game, most of them are upgraded versions of other techs. For example, there are eight different Improved Industrial techs, running from Improved Industrial 9 down to Improved Industrial 2. There are ten Battle Computer techs, from Battle Computer II to Battle Computer XIII. The same goes for robotic controls, shields, engines, range, terraforming, and most of the weapons are simply number upgrades over other weapons (e.g. Lasers to Ions to Blasers to Fusion Beams). There are relatively few truly unique techs in Master of Orion, only a few things like the High Energy Focus or Hyperspace Communications. After accounting for all of the techs that are improved versions of other techs, I'd estimate that there are only about 30 actual techs in Master of Orion. This makes the game much easier to learn; if you know what ECM I does, then you know what ECM VIII does. By avoiding the detailed clutter that so many other games fall into, MOO can keep the focus on big picture strategy. This leads into the next major point.

The second thing that makes Master of Orion stand out is what ISN'T present in the game: a lack of unimportant time-wasting extras. There's very little in the way of gameplay fat in MOO. Every mechanic present in the game is vitally important to the greater whole, and there's almost nothing that could be stripped away without having a negative impact. I had to think for a while about what could be taken out of the game while doing the least harm, and the best I could come up with was some of the specials used for ship building. You could remove the Repulsor Beam or the Ion Stream Projector and the gameplay would be fine, albeit less interesting. But that's really all that came to mind for MOO, unlike most other titles where there are all sorts of unneeded additions that drag down the gameplay. I can't think of anything to remove from the planetary management, tech system, diplomacy, and so on. Maybe the ability to threaten other races? I dunno. There's very little waste of any kind in the gameplay mechanics of Master of Orion.

The comparison to other empire-building strategy games is again instructive here. Designers have a tendency to cram in all sorts of extraneous things that clutter up the gameplay and largely serve to waste the player's time. Let's use Civ4 again as an example of an excellent game that still struggles to shake this issue. Civ4's early game is the richest part of the gameplay, and there's little to distract the player from the core issues of exploration, research, expansion, and conflict over control of land and resources. However, further down the tech tree Civ4's gameplay begins to drag noticeably, especially in the Industrial and Modern eras. Since I worked on Civ4's development, I can relate firsthand how these eras didn't receive as much polish and attention to detail, largely due to issues of time. We did test the later eras, but by definition they were never going to receive as much focus as a standard Ancient era opening. (Everyone should be thankful for the Multiplayer games that were run on Industrial and Modern era starts, which caught a lot of potential issues before release. A lot.)

This wasn't helped either by the decision to add a whole bunch of rather pointless fluff in the two Civ4 expansions. The Apostolic Palace is a good example; it's a very poorly thought out mechanic, and largely used to cheese out undeserved religious victories in Single Player games. Beyond the Sword's gameplay would be improved by removing the wonder entirely. The idiotic coastal blockades are another good example. There's a reason we use house rules banning them for Multiplayer games. Don't even get me started on vassal states, the single worst gameplay mechanic introduced in the Civ4 expansions. Ditto for things like overseas "colonial" maintenance costs, the unbalanced and poorly implemented espionage system, and the dozen new lategame military units added in Beyond the Sword. Did Civ4 really need attack submaries, missile cruisers, and mobile SAMs? Of course not. This is called "extra stuff for the purpose of having extra stuff", the creation of additional content to help justify charging full retail price for an expansion. Content is created to fill out a series of bullet points for a press release on the back of the box, not because it fit organically within the gameplay design.

And that's using Civ4, which is an outstanding strategy game in its own right. Things get much, much worse if we look at other games in the empire-building genre for examples. Civ3 had useless things like coastal forts and civil defenses, the silly Wall Street interest mechanic, and radar towers cluttering up the map everywhere in the late game. The Galactic Civ games get bogged down with the minor races and endless tedious micromanagement of starbases. (The ability to put down a few starbases is cool; when you're spending all your time moving constructors around servicing dozens and dozens of starbases, it becomes busywork.) Civ5 is the current king of pointless time-wasting fluff, as almost the whole game consists of doing some kind of largely irrelevant activity while hitting Next Turn and waiting for things to happen. I'm not going to belabor this point, as I wrote a whole article explaining this in more detail, so it's enough to say here that if you enjoy managing city states and archaeological expeditions then Civ5 is the game for you. I'd say that Civ5 is the worst culprit here, except that I played Master of Orion 3, and that game was far worse. Nothing that you did in MOO3 had any impact on the gameplay; the entire thing was one long session of wasted time as you filled out DEAs that did nothing and researched techs that had no noticeable effect (see the screenshot above for an example). MOO3 looked like an Excel spreadsheet, and was about as much fun to play as one.

The whole point is that the original Master of Orion doesn't have anything like these systems. There are no minor races or city states to detract from the diplomacy with your actual opponents. There are no outposts or colonies to manage; either a planet belongs to you or it belongs to one of your rivals. There are no vassal states and no surrendering in diplomacy. Espionage is simple and direct: you tell your spies if you want them to steal techs, and if you succeed then you get to pick which field to pilfer. If your spies get caught, the AI usually declares war on your empire. High risks and high rewards. There's no need to do a whole bunch of tedious movement of spy units or fiddle with espionage points. Combat is similarly no-frills: you design your own ships, and all ships of the same type stack and move together. A simple rally point system allows the player to amass their fleet wherever they want. I can build 10,000 ships in MOO with ease, and move them to their destination with three mouse clicks in 0.5 seconds. The endless logistical nightmares of moving units in Civilization (or even Galactic Civ) are nowhere to be found. MOO cuts through the clutter and allows the player to focus on big picture strategy.

I believe that Master of Orion is a better game for eliminating the clunky extra mechanics and gameplay systems found in so many other titles. Not everyone would agree with this; in fact, the general belief on the Internet seems to be that more stuff = better when it comes to strategy games. I wrote a whole article about this previously, explaining how additional complexity isn't necessarily good or bad - only more complex. For strategy games, the goal is to achieve DEPTH, which may or may not have anything to do with complexity. Too often both designers and the general public conflate these two together. Because Civ4 is this big complicated strategy game, everyone thinks that it's necessary to design equally big and equally complicated strategy games in the same model. If 20 leaders are good, then 30 leaders are even better. Why stop at 80 techs when you could have 300 techs? More of everything, more more more!  It's an unfortunate mindset.

It's an unfortunate mindset.

This leads us into the discussion of why we're never getting another game like Master of Orion.

The economics of creating games have changed over time. The earliest games from the 1970s and 1980s were often the work of a single individual, one person who would do everything from programming to art design to sound. With little in the way of past precedent, there were all sorts of bizarre and creative ideas that eventually turned into beloved games. (For example, think how weird Super Mario Brothers must have appeared in 1985. Magic mushrooms, glowing stars, goombas, evil turtles, beanstalks that grow into the clouds - what kind of acid trip was this?!  ) Of course many of the early games were terrible, experimenting with gameplay ideas that didn't work or went nowhere, but that was all part of the growing pains of a young and immature industry. Games didn't need to be realistic because the limitations of the hardware made that essentially impossible. As a result, the imagination of designers ran free and wild. When most games were being created by a single guy in his basement or garage (and it was almost always men at this time), the only restrictions were what could be done with the hardware itself.

) Of course many of the early games were terrible, experimenting with gameplay ideas that didn't work or went nowhere, but that was all part of the growing pains of a young and immature industry. Games didn't need to be realistic because the limitations of the hardware made that essentially impossible. As a result, the imagination of designers ran free and wild. When most games were being created by a single guy in his basement or garage (and it was almost always men at this time), the only restrictions were what could be done with the hardware itself.

By the late 1980s and into the early 1990s, the individual developer had largely been replaced by small teams. Creating games simply required too much work for one person to handle, with the result being that there was now one person assigned to produce the project, several people picked for programing, one person for music and sound, etc. This era is often seen as a golden age for gaming, and I think there's some truth to the notion that working in a small team of roughly a dozen people tends to be a good fit from a logistics standpoint. On the other hand, people who are in their 20s and 30s today grew up playing games from this period, so it may also simply be nostalgia at work. Fun fact from a historian here: for the vast majority of people, "the best music ever" just so happens to be whatever was being produced when they were 15-25 years old. Funny how that works out...

In any case, as the budgets for individual games grew larger, more and more people continued to be assigned to work on each project. By the mid to late 1990s, the proliferation of CD-ROMs meant an increasing reliance on full motion video and orchestral sound. The growing cost of these games meant that the days of the individual designer were over. Even teams of developers were often unable to raise the investment capital necessary for new projects. Increasingly designers were forced to turn to large publishers who would supply the money needed to back their games, and there was a massive period of consolidation in the gaming industry between roughly 1995-2005. Say goodbye to small independent groups like Microprose (Civilization), Simtex (Master of Orion), and Maxis (SimCity). Say hello to Take-Two Gaming, Atari/Infrogames, and Electronic Arts/EA, the three publishers who purchased each of these beloved strategy titles.

Despite putting "games" in their company titles, many publishers have traditionally had little to do with actual game development. They're investment groups that back gaming developers in the hopes of making a profit, nothing more or less. As the budgets for games have continued to spiral out of control over the past decade, with staff running into dozens or even hundreds of people and costs exceeding one hundred million dollars in some cases, publishers have demanded greater say over the content being produced. I don't blame them for that; if you were fronting that kind of money, wouldn't you want some control over the game under development? Unfortunately all of this comes at a cost: no one is going to risk that kind of cash on a new, untested idea. Publishers want something nice and safe. Thus the public has been getting an endless sea of sequels, remakes, reboots, and otherwise reimaginings of the same old games from decades earlier. This is exactly the same phenomenon that's happened to movies, of course, with the same economics at work. No one wants to risk $500 million making a new superhero movie that might flop when they can make the eighth Superman film or the sixth Spiderman film. Games are "franchises" now, commoditized brands to be exploited as long as the public remains interested. EA seems content to keep making the same three sports games until the end of time, and they'll never face any competition since they own monopolies on the official team licensing. Activision snaps up the rights to anything popular, relentlessly saturates the market with games until the public loses interest (see: Tony Hawk, Guitar Hero, Call of Duty, etc.), and then moves onto the next franchise that can be exploited. It's thoroughly depressing to watch.

Of course it's easy to blame the publishers for the ills of the gaming industry. Developers are too often let off the hook, and they are in many ways equally culpable. Designers are often guilty of trying to create projects that are far beyond their means, resulting in wildly unrealistic timelines and missed deadlines. There have been way too many Daikatana projects and Peter Molyneux titles, and publishers aren't the ones at fault in these cases. Many designers seem content to work on refining and polishing their creations indefinitely. Without a publisher to hold their feet to the fire, nothing ever gets finished, as many recent Kickstarter vaporware projects will attest. In many of these cases, it turns out there was a good reason why no publisher was willing to fund the project.

Anyway, the point of all this is less to find fault with modern gaming and more to emphasize the simple fact that the landscape has changed over time. The days of a major development studio creating a new game with only a handful of people on staff are long gone, and they're never coming back. For example, back in 1991 there were only about a dozen people who worked on the original Civilization. Sid Meier did virtually all of the design work himself, and the Microprose budget had to have been miniscule. Twenty years later, there were at least ten times as many people who worked to create Civ5, and probably more than that when counting all of the testers and support staff between both Firaxis and Take-Two. We have no exact numbers for Civ5's budget, but rumor places it somewhere between $20-$25 million, with several million dollars set aside for advertising and promotion. With that kind of money involved, it's actually quite surprising that a game like Civ5 has as much innovation as it does. (I've certainly criticized the game over the years, and to Civ5's credit it doesn't play things safe with the mechanics. They just don't work that well in practice.) Most publishers do everything possible to avoid rocking the boat, revamping the same gameplay over and over again with each new title in a series. Have fun doing the exact same quests in Assassin's Creed #17, this time in a slightly different city! You get the idea. Due to the big sums involved, there's every incentive possible to keep things bland and familiar.

Just as ever-more expensive movies must appeal to bigger and broader audiences, the same thing applies to gaming as well. Superhero movies are omnipresent these days because they're easy to make, involve familiar characters (why bother establishing a new character when you can simply make another crappy Transformers film?), and have simple plots that play well internationally. Because humor is so culturally-dependent, big budget comedies have almost completely disappeared over the years. Too much risk that the movie will flop in China and fail to make its cost back. Games are no different; the gaming equivalent of the superhero film is clearly the first-person shooter, also easy to make and popular across the West. When the latest Call of Duty games are supposedly spending $20 million just on advertising alone, they can't exactly aim for niche audiences. The result is again games designed to appeal to the widest audience possible, games often devoid of any kind of nuance or subtlety. These mass-market games can't be particularly frustrating or challenging either; you wouldn't want that 13 year old kid getting upset and returning his purchase to the store, would you? Better to make everything almost comically easy to figure out, put tutorials everywhere, and if the player wants more challenge, well, they can always go online for PvP multiplayer. (What happens when young and not-so-young players who are used to winning at everything suddenly come up against the reality that they're not particularly skilled online? The endless ragefests that we all know only too well.)

So why does this matter? I would argue that the original Master of Orion is so brilliant precisely because it went in the opposite direction from virtually every trend currently taking place in the gaming industry. It was done by a small team (I think about ten people) working on a small budget in the early 1990s. Good luck seeing anything like that from the "full HD / full voice acting" MOO 2016 reboot! At a time right now when every game wants to emphasize how many doodads and extra bells and whistles can be crammed into the product (hello blatantly unnecessary DLC!), Master of Orion was a relentlessly streamlined experience, cutting out everything extraneous. I don't even think it would be possible to replicate the original design in today's marketing environment. Can you imagine if the design team of MOO 2016 went to their publisher Wargaming and said, "We're only going to have one victory condition, the Galactic Council, and that's it." Something tells me the publisher wouldn't be too pleased. They would probably say, "Only one?! Civilization has five victory types, we need AT LEAST that many!" And that would miss the point entirely, since the simple dynamics of MOO's Council setup are outstanding. Adding a tech victory and an economic victory and an "excellence" victory doesn't improve the gameplay - it detracts from it. But due to the way that modern game design and marketing efforts work, those extra victory types will always, always have to be added. MOO 2016 is competing with Civ5 and Galactic Civ 3 and all the Paradox strategy titles, so anything in their games must also be in this one, good gameplay fit or not. The marketing blurbs define the gameplay, not the other way around.

Master of Orion's greatest genius lies in how it REMOVES options from the player, not adds to them. Technologies are randomly missing from you tech tree in every game, forcing the player to work around their absence. Tech trading with the AI races is strictly limited; you can ask them for one of their techs, but they pick what they want from you in return, and there's no haggling. Take it or leave it. Because of the limitations present in the system, there's no microing for every last penny or crazy tech brokering. The lack of options actually make the system better. Similarly there's no magical instant-rush production, no colony ships appearing out of thin air like the early game of Galactic Civ. At most you can double a planet's production on any one turn with the Reserve system, and that's it. There's no "whoops, I didn't see that attack coming, I'll sell a bunch of old techs for thousands of gold and rush-buy an army to defend." If you fail to anticipate threats in Master of Orion, there's rarely enough time to do anything about them when they appear.

Or consider diplomacy - there are six personality traits that the AI can get in Master of Orion. One of them is "Erratic", which means that the AI leader will randomly declare war at times due to dice rolls. They're fair about this and will attack other AIs as much as the player, but their attacks are completely random. This sounds like a terrible idea, taking war or peace completely out of a player's hands! And it would be, if all of the AI leaders were Erratic. More typically, there will be one of these opponents in each game, occasionaly two of them. It's certainly a unique approach to diplomacy. However, this is yet another ingenious mechanic that serves to shake up the MOO gameplay. By setting a small number of AIs to Erratic status, the game forces the player to adapt. You know (ahead of time, remember - AI personality is always visible upon first contact) that one opponent cannot be trusted to stay peaceful, ever, no matter what you do. By taking the possibility of permanent peace off the table with certain opponents, the gameplay becomes much richer and more interesting. The diplomacy would be lousy if all the AIs played this way, but other ones are Honorable, and others are Pacifists, and so on. It's the limitation of player options, taking certain things off the table, which makes the whole system work so well.

Again, can you imagine a modern strategy game that worked like this? I can just imagine the E3 press conference: "We're going to build a diplomatic system where the player has very few options available. And sometimes the AI will just declare war due to random dice rolls, nothing you can do about it. The techs you want to research may or may not be present in your tree. Once you pick a tech to research, you can't change your mind later. Oh, and to keep things streamlined, we're going to limit you to only six ship designs at any point in time. If you want a new one, you have to scrap some of your current ships. Questions?"  Any designer that proposed this would get cruficied in the gaming media, not to mention face a revolt from their publisher. It simply can't happen any more. No, every modern strategy game from a major publisher has to fill out the same feature list, because not having those features would be seen as cause for alarm. No one would even consider CUTTING features and removing entire gameplay systems to achieve superior gameplay. I don't think that any designer could get away with the kind of cutting necessary to create another Master of Orion. At least, not from a major publisher or designer.

Any designer that proposed this would get cruficied in the gaming media, not to mention face a revolt from their publisher. It simply can't happen any more. No, every modern strategy game from a major publisher has to fill out the same feature list, because not having those features would be seen as cause for alarm. No one would even consider CUTTING features and removing entire gameplay systems to achieve superior gameplay. I don't think that any designer could get away with the kind of cutting necessary to create another Master of Orion. At least, not from a major publisher or designer.

If there is hope, it lies with the proles indie designers.

For the various economic reasons outlined above, we will never get another Master of Orion from a big studio. There are simply too many budgetary pressures working against it. The only chance would be from some kind of indie developer, where an individual person or a small team would be able to recreate the same development environment from the 1980s. Working in their spare time or with minimal financial backing, we might see someone come up with something brilliant and unique once again. Let me be clear: this is not an ode to the wonders of indie development. Most indie games are frankly terrible, since the designers are often producing vanity projects designed to appeal to themselves, not intended for sale on the market. I'm extremely skeptical of Kickstarter projects, I've never backed any of them, and I have no intention of doing so in the future. My point is rather that the theoretical potential for another truly innovative and unique strategy game lies there, outside the backing of major studios, and that's the only way that we would see another Master of Orion. We know it's possible because it's already happened.

The obvious example here is FTL: Faster Than Light. While not an empire-building strategy game, FTL achieves its own gameplay success in much the same way as the original Master of Orion: by cutting out everything unnecessary and focusing intently on what's left over. People always ask me on Livestream what should be added to FTL, or what should be included in FTL2, and I always respond the same way: nothing. The game doesn't need anything else. If anything, the Advanced Edition expansion already comes close to packing in an excess of content. Adding further content (like that laughable Captain's Edition mod) would only make FTL a weaker game, not a stronger one. Remember, more content and more complexity doesn't equate to more depth. As the Saint-Exupery quote at the beginning of this article stated, the sign of true excellence in design is when there's nothing that can be removed, and FTL hits very close to that ideal. In my opinion, FTL is the single best strategy game released in the last five years, precisely because it's relatively simple to play and has such razor-sharp balance, even more impressive given the randomized nature of the gameplay. Nearly every run is winnable for an expert player, the replay value is extremely high, and success or failure is determined by your actions, with just enough RNG element to make things interesting. What more could anyone want from a truly outstanding strategy game?

Anyway, I'll keep an eye on the MOO reboot. Perhaps we'll all be pleasantly surprised this time next year when it releases. More likely, I'll still be playing the 1994 release and waiting for the next FTL, whatever form it might take. Thanks for reading.