I grew up as an Orioles fan in the suburbs of Baltimore. Both of my parents loved sports, playing on athletics teams when they were in high school and college, and they passed on that love to both of their children. Living in Baltimore in the 1980s and early 1990s, the Orioles were the only professional sports team in town. The Colts had left for Indianapolis when I was an infant and the Ravens wouldn't arrive until I was 14 years old in 1996. During the intervening span of time my home city was left with just the Orioles, and it was the professional baseball team that dominated my formative years from a sports perspective. We barely watched the NFL at all during these years, and the league's attempt to turn Baltimore sports fans into Redskins supporters was vehemently rejected by Baltimoreans. Professional basketball or hockey or soccer never even entered into the conversation. It was the slow, deliberative rhythms of baseball that I grew up watching, instilled into me over the course of hundreds and hundreds of games broadcast on local television. The Orioles teams of this era were decent but not great, putting up a good fight before ultimately succumbing to the powerhouse team of this era, the Toronto Blue Jays. Longtime Orioles fans still carry a grudge against Blue Jays manager Cito Gaston, who infamously refused to put Orioles pitcher Mike Mussina into the 1994 All Star Game when it was played in Baltimore for no apparent reason other than to spite the hometown fans. I learned to root for the orange and black in much the same way that I learned the multiplication tables or the state capitals. It was simply part of life for a young boy growing up in the area.

If I liked baseball, then the only fair way to describe things is that my dad loved baseball. He was always eager to teach me and my brother the ins and outs of the sport, how to hit and throw and catch and everything else that went along with them. I'll always remember my dad watching the Orioles games every night on the TV in his office down in the basement, yelling excitedly or angrily along with the action taking place on the field. My dad was a pitcher by trade, and he had pitched for the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC) baseball team in its inaugural year of existence in 1966. He tells the story that he was the pitcher to earn the first win in the college's history, which may or may not be true due to the way that stories tend to grow over time. My dad still loves to talk through an individual at bat from a pitcher's point of view, explaining how to throw pitches in sequence to fool hitters and making suggestions about what the next pitch should be. He can read the signs put down by the catcher on the TV broadcasts and often predict what's going to be thrown next. The long and short of it is that my dad is a baseball lifer, and love for the game is etched in his bones.

When my dad retired from full time work at the age of 65, we held a big retirement party with family and friends to celebrate. The biggest gift came from my brother: a ticket for my dad to take part in Orioles Dream Week. This is an event put on by the team for diehard fans, granting them a chance to travel down to the spring training complex in Sarasota, Florida and spend a week playing a series of baseball games with retired former players. The Dream Week participants get full uniforms, use the team practice facilities, have access to the team's training staff, and get to hobnob with a bunch of former players that they probably grew up watching in the field. After the weeklong event concludes in January, the participants get to come back for one more reunion game in June that takes place at Oriole Park in Camden Yards. None of this comes cheap and the price was about $4000 per person (in 2014 dollars). But we had always thought that this would be a perfect retirement gift for my dad and we were able to make it come true thanks to the extremely generous contribution from my brother.

My dad went down to Sarasota for the Dream Week event by himself. He had a very good time taking part in the baseball games there, with the one complaint that they probably played a few too many of them. I believe that the schedule had two games per day for five straight days, something along those lines, and it probably would have been better to have only one game per day. Most of the participants at Dream Week are men in their 40s, 50s, or 60s and not surprisingly everyone quickly becomes sore and exhausted. These are real baseball games, by the way, on full 90 foot diamonds and standard pitching mounds. The biggest difficulty is finding enough participants to pitch all of those innings without destroying the arms of a bunch of amateurs. My dad pitched for a couple of days and then was so sore that he could barely throw a baseball afterwards. His Dream Week team was coached by Rick Dempsey, a former Orioles catcher who had been the MVP of the 1983 World Series in an otherwise fairly pedestrian career. Dempsey was well known to Orioles fans due to his work on the television broadcasts for the regional MASN sports network that does the Orioles and Nationals baseball games. I think that my dad's favorite part of Dream Week was less the actual baseball games and more so the time spent with former players like Dempsey, asking questions and swapping tales about remembered players and games from yesteryear.

When the reunion game took place in June, our whole extended family came to see the action take place. My cousin and her kids drove down to show their support while my brother flew in from Chicago for the weekend. One of the best things about the Dream Week event is the chance to play this reunion game in Camden Yards itself, one of the most beautiful and iconic venues in which to watch a baseball game. This event is open for anyone to attend free of charge, although in practice it's pretty much just the families and friends of the Dream Week participants who show up. I've been to Camden Yards many times before, but rarely on an early Satuday morning with the stadium devoid of visitors. It's bizarre to have about 200 people sitting in the seats of a stadium that can accomodate 40,000 fans. On the plus side, we were able to sit anywhere that we wanted in the lower deck and enjoyed perfectly clear views of the field.

My dad has always gone by his nickname of "Rock", which is a pun off of our last name, and that's what they put on his uniform at his request. The full dress uniform makes anyone look fantastic, and I could have been convinced that my dad was a bench coach or something like that for the real team. It was a good thing that this game was scheduled so early in the day since those uniforms did look awfully hot. My dad's team went by the name of the Dippers, and they were playing the team coached by Mike Boddicker known as the Bodd Squad. The Dippers had the privilege of being the home team and getting to wear the home whites by virtue of having a better record during the Dream Week competition. This meant that my dad's team was using the Orioles dugout instead of the road team's dugout, and we seated ourselves behind it on the first base sideline. The Dippers took the field first, everyone lined up for the playing of the national anthem, and at 9:00 AM the game was underway.

Watching amateur athletes playing a baseball game in a real major league stadium is a surreal experience. Quite aside from the sea of empty seats ringing the playing field, the use of the official team uniforms for the players has a way of distorting expectations. At a casual glance it looks like those are professional baseball players out there on the field, but watching the action for any length of time reveals the huge gap in performance between professionals and amateurs. The Dream Week participants ran like ordinary people, threw like ordinary people, and fielded like ordinary people, despite all of this taking place in one of the great baseball cathedrals. There were quite a few fielding blunders and some very, very slow runners out on the basepaths. The umpire also had to call a very generous strike zone to ensure that the game wasn't an endless parade of walked batters. More than anything else, it really drives home how ridiculously talented the professional players are at their craft. We take it for granted that the shortstop will be able to field a grounder and throw out a batter sprinting up the first base line, but in this game every roller to the left side of the infield was an adventure, even with much slower runners on the basepaths.

The rules for this game were a lot less strict than in a real baseball game, and the Dream Week participants were able to move around from one position to another between innings. My dad started out as the first base coach, then moved to right field for the next inning. He said afterwards that he was praying no one would hit the ball into right field while he was out there, and fortunately no one did. When it was time to bat, my dad showed a judicious eye and ended up drawing a walk before being forced out at second by the following batter. The Dippers did end up scoring though, and took an early lead over the Bodd Squad. They would spend most of the game trying to make that lead on the scoreboard hold up.

Of course, my dad had the opportunity to take his turn pitching an inning as well. Back when he was in college, my dad had thrown in the low 80s (that's miles per hour for non-baseball fans) and had a particularly good curveball that he often used as his strikeout pitch. When our family visited the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York when I was about ten years old, he had been able to throw a pitch in the 70s on the radar gun that accompanied one of the museum exhibits. Pitching on this day at age 66, my dad couldn't throw at anywhere near that velocity any longer and had to rely on craftiness and pitch placement to get batters out. He walked a pair of batters but managed to get through the inning without giving up a run, including getting one person on the other team to strike out. In what was likely his last time ever pitching in a competitive baseball game, my dad managed to come in and throw a clean sheet against players who were mostly decades younger. We couldn't have been prouder.

My dad ended up batting two more times in the game... and drew two more walks. His final slash line was therefore 0.000 / 1.000 / 1.000, three walks in zero official at bats, which was some kind of utopian ideal of Moneyball sabermetrics. He was batted in and scored a run in his second trip on base before being forced out at second again in his last trip around the bases. My dad's hip had flared up in the wake of his Dream Week excursion down to Florida, and it was continuing to prevent him from being able to run during this game as well. The pain was serious enough that my dad went to the doctor afterwards and found out that he needed to have hip replacement surgery, which took place the following year. We were quite fortunate that my brother had put together the Dream Week gift when he did, as my dad likely wouldn't have been able to take part in this if we had waited any longer. The spirit was willing but the body couldn't quite keep up.

The Dream Week participants were almost entirely men, and the event is geneally geared around the assumption that the participants will be male. However the Orioles do allow women to take part if they're willing to pay the hefty entry fee, and the Dippers had one woman on their team. Milligan pitched for an inning, batted, played in the field, and was generally indistinguishable from the other amateurs on the roster. She looked like she was having a lot of fun from what I could tell. Most of the players didn't particularly stand out in terms of talent, but one exception was the guy named Tindal in the pictures above. He pitched for two innings and completely shut down the Dippers, throwing in the mid 80s and tossing the baseball right past the batters on my dad's team. It was a stark contrast between the other amateurs out there who were pitching in the 50s and 60s and then a fireballer coming in and tossing that much faster. The Dippers never had a chance.

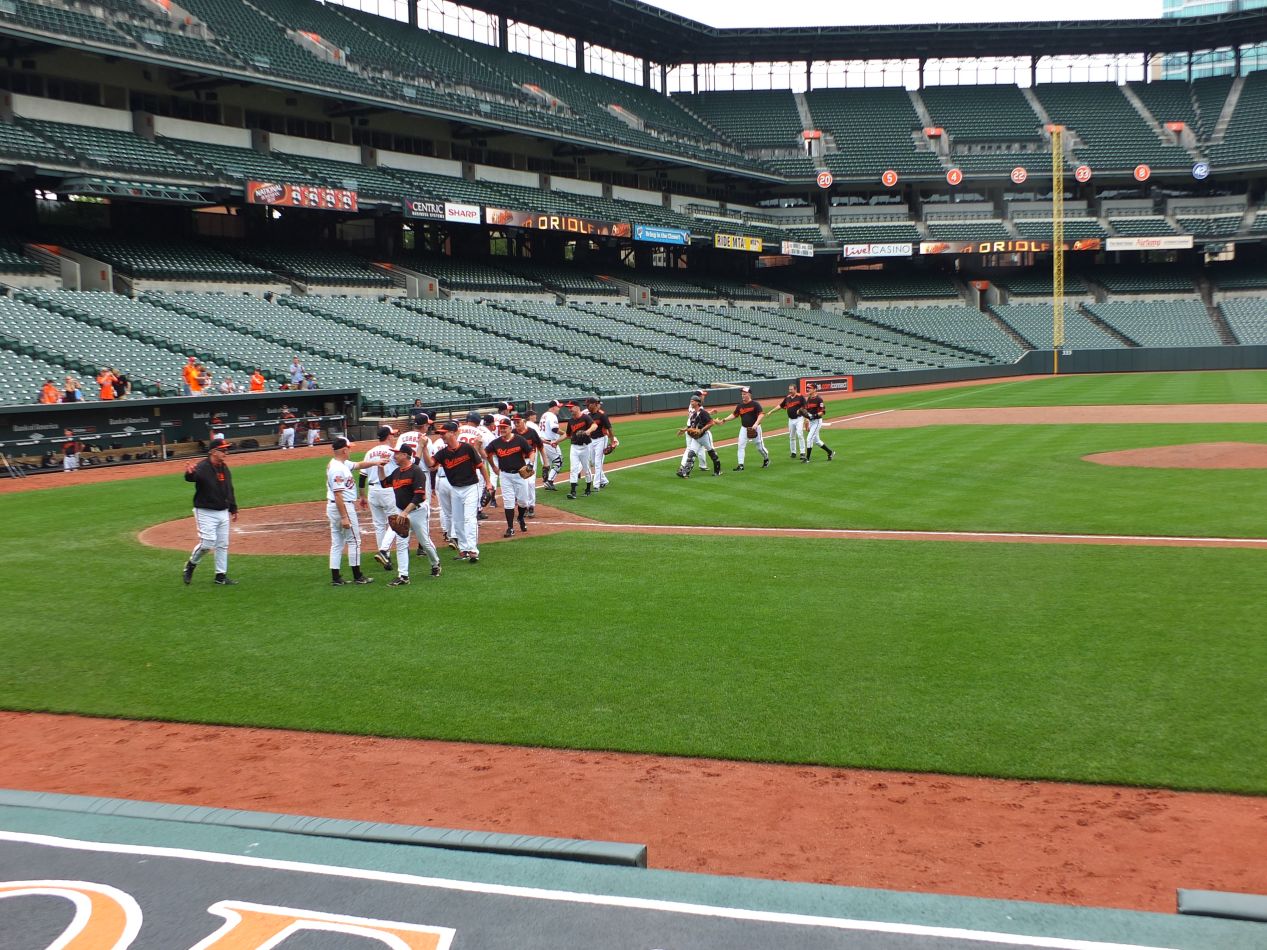

Ultimately the Dippers were unable to hold onto their lead. Several costly errors in the field allowed the Bodd Squad to take the lead, and then their closer mentioned above came in and shut the door. The reunion game was therefore a loss but no one seemed to mind too much. The two teams exchanged the traditional handshakes in front of home plate, then the Dippers huddled one final time before walking off the field. This was one of the happiest teams that I've ever seen after a loss. If there was ever a team that was "happy to be there" as the old sports saying goes, it was this one.

This was after the game finished, with my brother, dad, and mother talking with one of our neighbors who had driven into Baltimore to see the game. Everyone who came out to watch seemed to have a great time, and it was a truly fun way to celebrate the game of baseball. My dad was very sore afterwards but highly pleased with how he had done. None of the Dream Week participants wanted to make a fool of themselves in front of their friends and families, and my dad certainly hadn't done anything of the sort. This was one of the best experiences that I can imagine for someone who loved baseball, and it was the perfect retirement gift for my dad. I'm so pleased that we were able to share a part of the experience with him at a place like Camden Yards. Our family was in the stadium the night that Cal Ripken broke "The Streak" for his 2131 game in 1995, and while this Dream Week game wasn't anywhere near as historic, it had a lot more personal meaning for us. Here's to many more afternoons spent enjoying a baseball game together in years to come.